The race to replace the ISS: Can Vast’s Haven-1 keep America in orbit?

October 20, 2025

As the International Space Station (ISS) approaches retirement in 2030, a quiet but high-stakes race is underway in low-Earth orbit.

Without a US replacement ready in time, China’s Tiangong space station could soon become the world’s only permanently inhabited orbital outpost, a symbolic and strategic shift that has added urgency to NASA’s efforts to foster a new generation of commercial space stations.

For nearly a quarter of a century, the ISS has hosted humans continuously, a joint effort between the United States, Europe, Japan, Canada and Russia.

Since November 2000, at least one American has always been in space, conducting experiments that have reshaped scientific understanding in fields as varied as medicine, materials, and climate research.

But as the ISS ages and costs rise, its partners are preparing for a controlled deorbit over the Pacific in 2030. NASA’s challenge now is to ensure that the United States and its partners do not lose their orbital foothold.

How NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations programme will replace the ISS

NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) programme is designed to prevent a “space gap” after the ISS’s retirement.

The initiative aims to shift the US presence in orbit from government-owned platforms to privately owned and operated stations, where NASA will be a paying customer rather than the sole operator.

In 2021, NASA awarded more than $400 million in seed funding to companies developing commercial station concepts. The agency has since launched Phase 2 of the CLD programme, which will select firms capable of hosting four astronauts for at least 30 days in orbit.

These stations must meet NASA’s rigorous safety standards and demonstrate reliability before the ISS is retired.

This public–private model mirrors NASA’s successful partnerships for cargo and crew transport with SpaceX and Boeing — a model that has saved billions while stimulating a competitive US space industry.

Vast’s Haven-1 aims to become the first commercial space station

Among the companies leading the charge is Vast, a California-based aerospace firm building Haven-1, described as the world’s first commercial space station.

The single-module platform is expected to launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in 2026, four years before the ISS is scheduled to deorbit.

Weighing around 14 tonnes, Haven-1 will host up to four astronauts on short-duration missions of around ten days. Over its three-year service life, the station will support roughly 160 astronaut-days devoted to research, manufacturing, and technology testing in microgravity.

At Vast’s Mojave, California facility, engineers have completed the final weld on the station’s primary structure and applied its first layers of protective paint. The next stage will integrate a domed viewing window and docking hatch, followed by pressure and load testing.

The company’s Haven Demo mission, planned for later this year, will validate key systems including propulsion, power, flight control, and ground software — the technical backbone for Haven-1’s operations.

Vast Haven-II: Potential successor to the ISS

Starting in 2028, Vast plans to launch Haven Modules every six months, with a final station configuration targeted for 2032.

“Safe, reliable, and low cost, Haven-II will introduce groundbreaking opportunities to expand human progress on Earth and shape the future of life in space,” CEO Max Haot said. “To continue crewed operations in low-Earth orbit before the ISS is retired, Haven-II will be built on the heritage of Haven-1, with key upgrades.”

Haven-II will feature two docking ports, a total mass of 29 tonnes, and support 720 crew-days. It will start with a single module launched on a Falcon Heavy as soon as 2028, five metres longer than Haven-1 and with twice the usable volume.

Launching in 2028 would ensure overlap with the ISS, guarding against potential disruptions such as an early Russian withdrawal from the partnership.

Inside Vast’s human-centred space station design

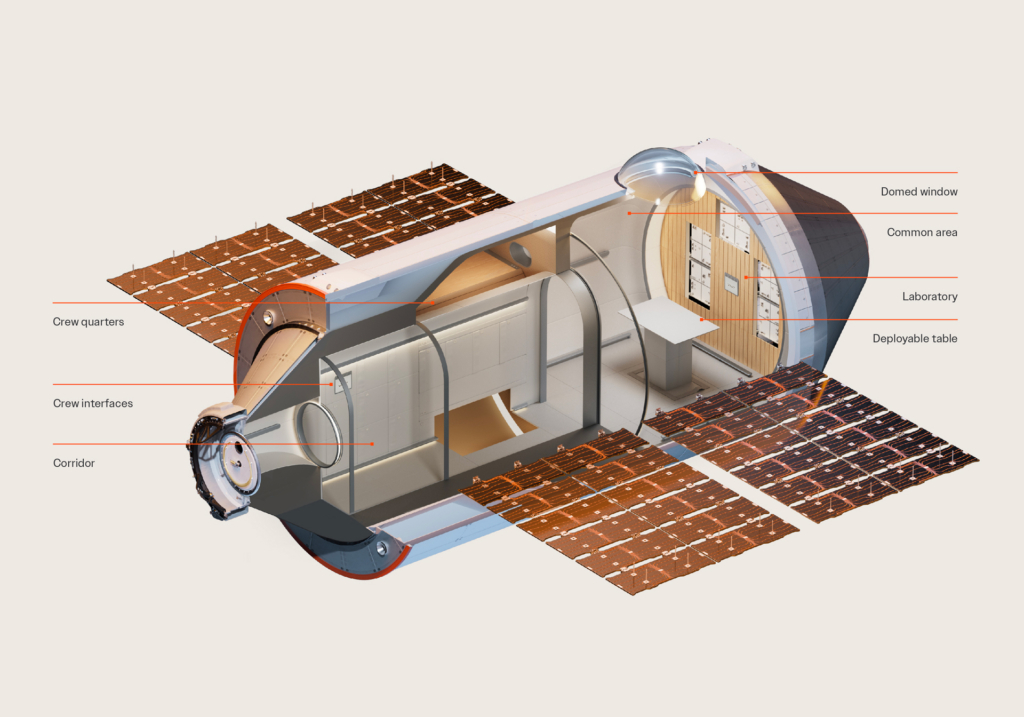

Vast recently unveiled interior renders of Haven-1, calling it a “human-centric industrial design” that blends functionality with comfort.

Features include a 1.1-metre domed viewing window, an integrated exercise system, a multi-use common area, and fire-resistant maple veneer slats that provide warmth and visual appeal.

The company has also developed a patent-pending sleep system to deliver customised support and improve rest quality for astronauts during extended missions.

Haot said Vast’s mission is to ensure that the United States maintains a permanent human presence in low-Earth orbit once the ISS retires.

“An American heartbeat has been in orbit every day for 25 years, and it must remain through and after the ISS-to-CLD transition,” he said.

Haot added that Vast has invested nearly US $1 billion of private capital and employs about 1,000 people in the US.

“We are manufacturing the majority of our systems — from life support and avionics to power and thermal control — domestically for the first time in decades. This strengthens the industrial base and reduces reliance on foreign suppliers,” he noted.

Other contenders in NASA’s commercial station race

Vast is not alone in the race to replace the ISS. Axiom Space, based in Houston, has already begun launching modules that will attach to the ISS before forming an independent station later this decade.

Blue Origin and Sierra Space are developing Orbital Reef, a modular habitat for research and tourism, while Northrop Grumman has proposed its Free Flyer concept, leveraging its Cygnus cargo-craft heritage.

Elsewhere, Airbus is partnering with US company Voyager Space to develop, build and operate ‘Starlab,’ a successor to the ISS.

All of these projects are vying for NASA’s approval under the CLD programme — and for prospective commercial customers such as private research institutions and sovereign space agencies seeking affordable access to orbit.

China’s Tiangong space station expands its orbital footprint

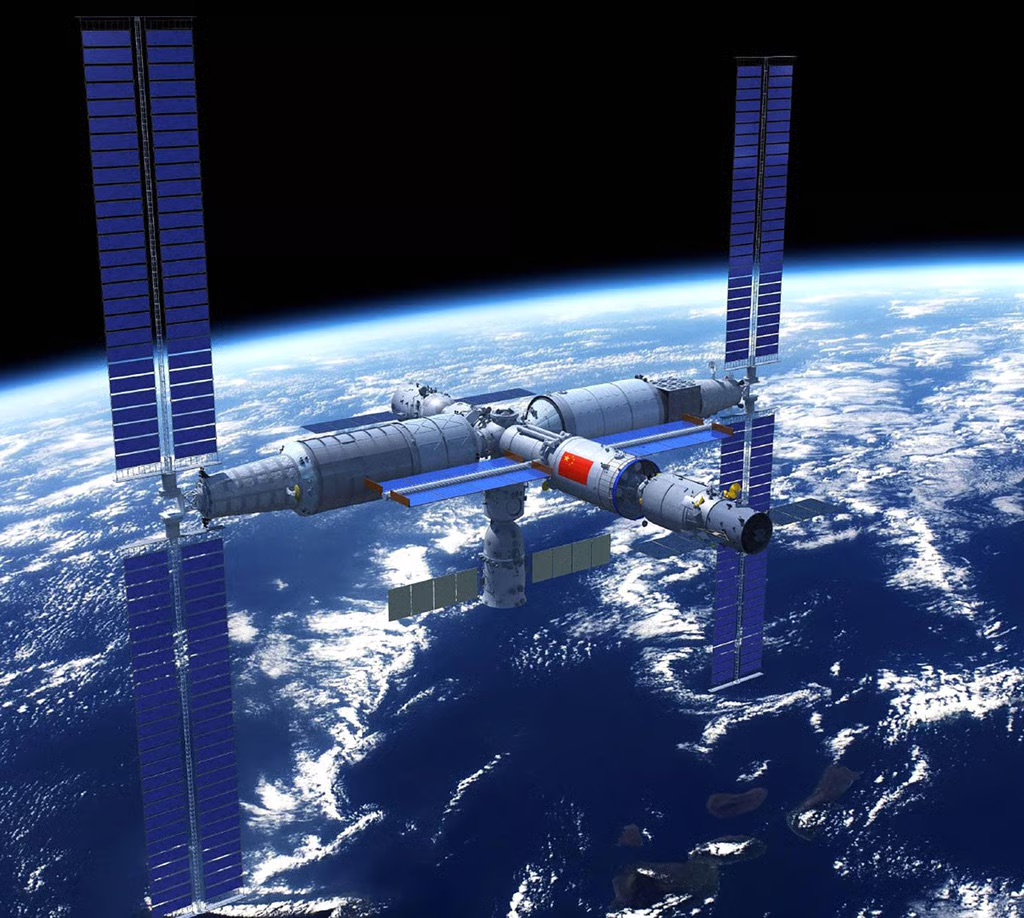

China’s Tiangong space station, fully operational since 2022, already maintains a three-person crew on six-month rotations at roughly 400 kilometres altitude, similar to the ISS.

Tiangong has become central to China’s human spaceflight programme, hosting experiments, satellite deployments, and in-orbit docking trials.

If NASA and its commercial partners fail to have a successor in orbit by 2030, Tiangong could become the world’s only inhabited space station — a scenario with implications for scientific collaboration, national prestige, and geopolitical influence in low-Earth orbit.

“By that time, it’s more capable than the ISS,” Haot said of Haven-II’s projected 2032 capabilities, “and we hope and expect more capable than anything China and Russia have in orbit at that time.”

The ISS legacy: 25 years of continuous human presence

Since its first modules launched in 1998, the ISS has become humanity’s largest and most complex engineering project in space. More than 4,000 experiments have been conducted aboard, generating over 4,400 peer-reviewed papers.

Research has ranged from cancer drug development to materials science and Earth observation. The ISS has also tested critical systems for future deep-space exploration, including life-support recycling, autonomous docking, and radiation shielding.

For many who have worked on or aboard the ISS, its end marks both the culmination of a remarkable international partnership and the dawn of a new, commercial era of spaceflight.

Under NASA’s CLD framework, the agency will transition from operator to customer, purchasing services aboard private stations. This model reduces public expenditure while expanding access for universities, startups, and international users.

Future commercial platforms are expected to host a mix of scientific, industrial, and even tourism activities, potentially forming a multi-station orbital economy over the next decade.

The road from ISS to Haven-1 and beyond

The coming years will be pivotal. The ISS is expected to remain operational through 2029 before a controlled deorbit over the South Pacific. NASA aims to qualify new commercial habitats and transfer research programmes before that point.

If Vast’s Haven-1 launches as planned in 2026, it will serve as the first bridge between the ISS era and private orbital stations. Its success will shape how human activity in low-Earth orbit evolves throughout the 2030s.

For NASA, the objective remains clear: when the ISS’s lights go out, a new American-built station must already be shining in orbit, continuing humanity’s 25-year presence among the stars.