10 hull losses in 35 years: The questionable safety record of the McDonnell Douglas MD-11

December 7, 2025

On 4 November, a UPS McDonnell Douglas MD-11 registered N259UP crashed whilst taking off from Louisville-Muhammed Ali Airport (SDF) in Kentucky, with the loss of all three crew members on board and 11 people on the ground.

All remaining MD-11s (around 60 according to ch-aviation) have since been grounded by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) while the investigation takes place into the accident.

Sadly, the accident was not the first resulting in the hull loss of an MD-11 since it first entered service in 1990. In fact, there have been nine other accidents involving the type since its entry into service. The type, along with the remaining DC-10s (and MD-10s still flying), has been grounded by the FAA pending an investigation by the National Transportation Safety Bureau (NTSB).

In this article, Aerospace Global News takes a look at the MD-11’s safety record over the past 35 years, examines whether the type will return to service and if not, is this the end of three-engined commercial aircraft?

The MD-11 – a brief history

The McDonnell Douglas MD-11 was designed to be a larger and more modern version of the three-engined McDonnell Douglas DC-10. The DC-10 first flew in August 1970 and was specifically designed as a high-capacity commercial airliner to serve the US transcontinental market. The DC-10 initially served with US carriers American Airlines and United Airlines.

Later, the initial version (the series 10) was upgraded with more powerful engines, long-range fuel tanks and additional centre main gear to handle the increased weight. The variant (known as the series 30) stretched the DC-10’s capabilities to transoceanic flight and allowed airlines to operate the aircraft between the US, Europe and Asia.

More airlines worldwide adopted the DC-10 once its capabilities had been extended, with the type proving popular in Asia-Pacific, Europe, Africa, South America, as well as the US. In all, 386 DC-10s were built for civilian operators, plus another 60 of the military variant, the KC-10, were also built.

The DC-10 was also made available as a dedicated freighter, and a combi version was also produced (DC-10CF). Many DC-10s were later converted from passenger to freighter aircraft for operators such as FedEx Express.

Toward the late 1980s, airlines such as American Airlines and Delta approached McDonnell Douglas about producing a larger and upgraded DC-10, with more powerful engines and greater range. The manufacturer eventually released designs for the MD-11.

The new tri-jet was a longer, more advanced derivative of the DC-10, with key differences including a stretched fuselage, longer range, raked wingtips, and a two-crew glass cockpit that featured digital displays instead of the DC-10’s three-person analogue cockpit.

The MD-11 also featured more powerful engines and advanced, computer-assisted flight controls. In all, a total of 200 MD-11 aircraft were built. Production took place from 1988 to 2000 in Long Beach, California, with the 200 aircraft being the final number delivered for all variants of the plane.

The 200 MD-11s that were built included various models, such as the standard passenger version, the MD-11F (freighter), the MD-11C (combi), and the MD-11ER (extended range). The first MD-11 was delivered in 1990, while the last was produced in 2000.

The last MD-11 passenger flight was on 16 October 2014, operated by KLM (KLM Royal Dutch Airlines). The flight was KL672 from Montreal in Canada heading to Amsterdam in the Netherlands – KLM’s home base. The type has found a second lease of life as a freighter, with around 60 still in service at the time of the UPS accident in November.

The MD-11’s safety record

Over the past 35 years of commercial service, there have been ten major accidents involving the MD-11 in which the aircraft has been written off as a result of the damage sustained. According to the Aviation Safety Network website, 139 other accidents or incidents have occurred involving MD-11 aircraft in this period.

As of November 2025, there have been 261 fatalities in the ten major hull-loss accidents involving the MD-11 aircraft, including both passengers and crew, as well as ground fatalities. These accidents have been attributed to various causes, such as pilot error, mechanical problems, and weather conditions.

The accident involving the MD-11 in Kentucky in November 2025 led UPS and all other MD-11 operators to ground their fleets “out of an abundance of caution,” while the National Transport Safety Board (NTSB) undertook an inquiry, which remains ongoing. Additionally, the FAA has ordered that all MD-11s remain grounded worldwide in the meantime and has issued emergency inspection directives.

The grounding and investigation of all MD-11s has renewed industry attention on the type’s ageing airframes and maintenance history, as well as its poor overall safety record.

Note: All aircraft accident data in this atrticle have been sourced from Aviation Safety Network.

MD-11 hull losses since 1990

31 July 1997 (FedEx Express, N611FE)

While landing after a routine flight at Newark-Liberty Airport (EWR), N611FE touched down 358 metres (1,175 ft) down runway 22R at 149 knots with a high descent rate. The aircraft bounced on touchdown, yawed and rolled right, touching down again 693 metres ( 2,275 ft) from the runway threshold.

The right roll pinned the aircraft’s right wing-mounted engine to the ground, possibly continuing until the right wing’s spars broke. The MD-11 skidded off the right side of the runway and ended up on its back some 1,463 metres (4,800 ft) from the threshold and just short of the airport’s Terminal B complex. The five crew members survived.

The cause was found to be the crew’s overcontrol of the aircraft during the landing and their failure to execute a go-around from a destabilised flare situation.

2 September 1998 (Swissair HB-IWF)

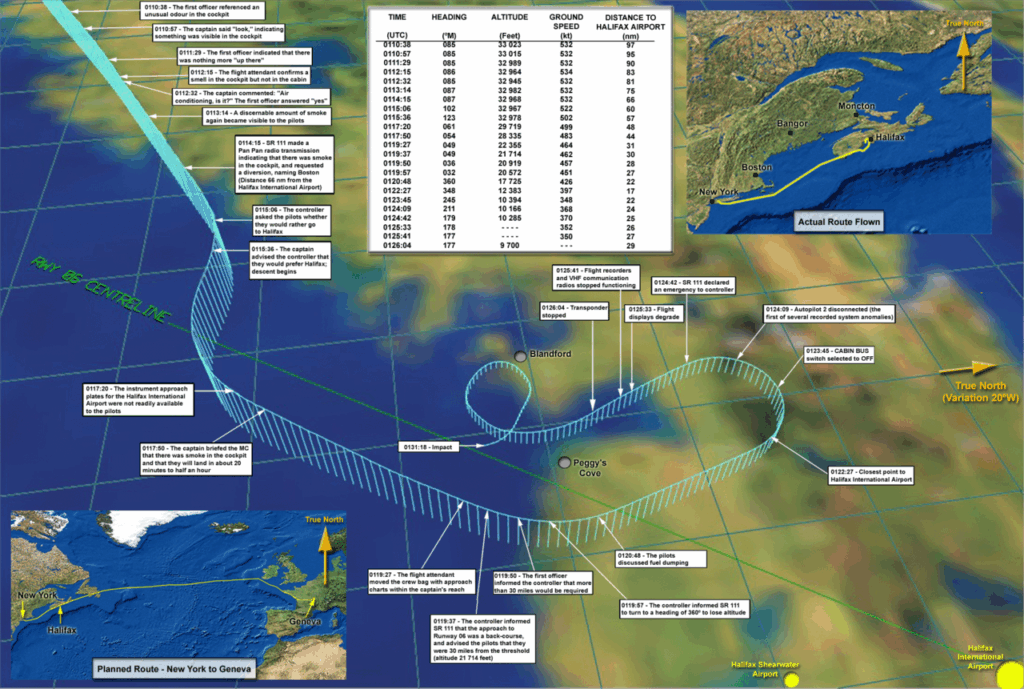

Probably the most well-known and most publicised of all the MD-11 accidents, Swissair flight SR111 had taken off from New York-JFK Airport (JFK) on a flight to Geneva, Switzerland.

Forty minutes later, the crew of SR111 contacted air traffic control, reporting that the pilots had detected an unusual odour in the cockpit and had begun to investigate. They determined that smoke was present in the cockpit, but not in the passenger cabin.

Four minutes later, the aircraft was 66 nm (122km) southwest of Halifax, and with smoke in the cockpit, the crew requested an immediate landing at any convenient airport. The pilots nominated Boston as their alternate, which was about 300 nm (600km) behind them.

Initially, the flight was directed towards Boston before later being offered Halifax Airport (YHZ) for an emergency landing. The crew was then given radar vectors to head directly to Halifax. The pilots then donned oxygen masks given the severity of the smoke.

The aircraft descended towards Halifax over the following few minutes, but was too high to approach Halifax’s runway from that point. The crew then elected to dump fuel with around 30 nautical miles (60km) to run. The flight was vectored to the south to dump fuel.

Around ten minutes later, both pilots almost simultaneously declared an emergency. The co-pilot indicated to the controller that they were starting to dump fuel and that they had to land immediately. Last radio contact was one minute later when the crew again declared an emergency.

By now, the onboard fire, which had started in the electrical equipment under the first class section, had propagated, causing severe disturbances in the aircraft control system and affecting the pilot’s ability to control the aircraft. In the last minutes of the flight, the electronic navigation equipment and communications radios also stopped operating.

The aircraft continued to descend over Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, until it struck the water in a 20-degree nose-down and 110-degree right bank. The aircraft was destroyed on impact with the water, with the loss of 229 passengers and crew.

15 April 1999 (Korean Air, HL7373)

The MD-11F cargo plane was operating flight KE6316 from Shanghai’s Hongqiao Airport (SHA) in China to Seoul, South Korea. The plane was loaded with 68 tons of cargo.

The engines were started, and following a routine take-off, the first officer contacted Shanghai Departure and received clearance to climb to 1,500 metres (4,900 feet).

When the aircraft climbed to 1,500 meters (4,500 ft), the captain, after receiving two wrong affirmative answers from the first officer that the required altitude should be 1,500 feet, thought that the aircraft was 3,000 feet too high.

The captain then pushed the control column abruptly and roughly forward, causing the MD-11 to enter a rapid descent. Both crew members tried to recover from the dive but were unable. The aircraft crashed into an industrial development zone around six miles (10km) southwest of Hongqiao airport. The plane impacted the ground, destroying several houses.

The cause was found to be a loss of altitude situational awareness resulting from altitude clearance wrongly relayed by the first officer and the crew’s overreaction with abrupt flight control inputs.

22 August 1999 (China Airlines operating as Mandarin Airlines B-150)

Flight CI642 had departed Bangkok (BKK) for a flight to Taipei via Hong Kong (HKG). The weather in the Hong Kong area was extremely poor with a severe tropical storm to the north of the airport, with gale-force winds and thunderstorms. Before the arrival of flight 642, four flights had carried out missed approaches, five planes had been diverted, and 12 planes had landed successfully.

Continuing with its approach, CI642 landed hard on its right main gear and the no. 3 engine impacted the runway. The right main gear separated, as did the right wing. The MD-11 then rolled inverted as it skidded off the runway in flames. It came to rest on a grass area next to the runway, 1,100 meters (3,500ft) from the runway threshold. The right wing was found on a taxiway 90 meters (300ft) from the nose of the plane.

#OTD in 1999: China Airlines Flight 642, a MD-11, crashes on landing at Hong Kong. 3 of 315 aboard died. Attempting to land during Typhoon “Sam”, landing gear collapsed, airplane rolled and caught fire. Crew´s actions and weather conditions were some of the factors in the crash. pic.twitter.com/emhjMEdzu6

— Air Safety #OTD by Francisco Cunha (@OnDisasters) August 21, 2025

Out of 315 passengers and crew, just three died. The crash sequence in this case bore similarities to a FedEx MD-11, which also flipped upside down on landing at Newark (see above) and the Tokyo-Narita Crash (see below).

12 October 1999 (FedEx Express N581FE)

FedEx flight 87 had departed Shanghai-Hongqiao Airport, China, on a cargo flight to Subic Bay International Airport (SFS) in the Philippines. En route at 11,276 meters / 37,000ft, about 43 minutes before landing, the MD-11 encountered moderate turbulence.

At that time, there was an airspeed ‘miscompare’ between the airspeed indicators of the captain and the first officer. The difference increased to 12 knots in about 90 seconds, causing the autopilot to disconnect, and increased to about 45 knots as the aircraft descended towards sea level.

Despite the crew later believing they had recertified the erroneous speed readouts, the aircraft continued its descent at a higher-than-normal descent speed. As the aircraft descended below 150 meters (500 ft), cues and warnings were ignored by the flight crew that strongly suggested the approach could not be completed within acceptable parameters.

The aircraft eventually touched down but could not be stopped on the remaining runway. It overran the end of runway 07, impacted an instrument landing system (ILS) antenna site, and continued off a ledge that dropped about 10 meters (30ft) onto a road located on the shoreline of the airport. The plane then entered the water and came to rest. The crew managed to evacuate the aircraft with slight injuries.

23 March 2009 (FedEx Express N526FE)

FedEx flight 80 departed Guangzhou (CAN), China, on a cargo flight to Tokyo-Narita (NRT). While the wind was gusting at Tokyo, it was not out of limits for the MD-11. However, on the approach, the aircraft became unstabilised with the aircraft’s autopilot and autothrottle system struggling to stay engaged.

Eventually, the aircraft crossed the runway threshold too fast, and the crew struggled to maintain the centreline. The pilot flying initiated the flare later than usual, and the aircraft touched down heavily before rising into the air again. The second touchdown saw the aircraft land nose-first, before the main landing gear touched down. The aircraft bounced once more before landing heavily.

On the third touchdown, the left wing attachment point to the fuselage fractured. The fuselage rolled to the left with the lift generated by the right wing, and a fire erupted. The aircraft rolled inverted and was consumed by fire. Both crew members were killed.

28 November 2009 (Avient Cargo Airlines Z-BAV)

The McDonnell Douglas MD-11F cargo plane, operated by South African carrier Avient Aviation, was destroyed when it crashed and caught fire on take-off from Shanghai-Pudong International Airport (PVG) in China.

Three crew members were fatally injured, while four survived the accident. Press reports indicate that the tail struck the runway before the aircraft crashed past the runway’s end. The aircraft was destroyed by the post-impact fire.

27 July 2010 (Lufthansa Cargo D-ALCQ)

A Lufthansa Cargo MD-11F cargo plane was destroyed when it crashed on landing at Riyadh-King Khaled International Airport (RUH), Saudi Arabia. Both crew members survived the accident.

Upon touchdown, the aircraft bounced with the main gear reaching a maximum height of four metres (12ft) above the runway with the spoilers deployed to 30 degrees. During the bounce, the captain pushed on the control column, resulting in an unloading of the aircraft. The aircraft touched down a second time in a flat pitch attitude with both the main gear and nose gear contacting the runway.

After two more touchdowns and associated bounces, the plane contacted the runway at a high descent rate. At this point, the aft fuselage ruptured behind the wing trailing edge. Two fuel lines were severed, and fuel spilt within the left-hand wheel well. A fire ignited and travelled to the upper cargo area.

The captain attempted to maintain control of the aircraft within the runway boundaries. Not knowing about the aft fuselage being ruptured and dragging on the runway, the captain deployed the engine thrust reversers.

The aircraft then veered towards the left side of the runway. As the aircraft departed the runway, the nose gear collapsed, and the aircraft came to a full stop 2,682 meters (8,800 ft) from the threshold of the runway and 91 metres (300 ft) left of the runway centreline. The mid portion of the aircraft was on fire by this point, and the entire aircraft was eventually destroyed.

13 October 2012 (Centurion Air Cargo N988AR)

Operated by Centurion Air Cargo, N988AR sustained substantial damage in a landing accident at São Paulo Campinas-Viracopos International Airport (VCP) in Brazil. Flight WE425 was operating a cargo flight from Miami International Airport in the US.

When the aircraft was cleared to land, the wind strength was 20kt, with peak gusts at 29kt. Upon touchdown, there was a total collapse of the left main landing gear, and the aircraft skidded along the runway for 800 meters (2,600ft) before coming to rest, sustaining substantial damage to the left landing gear, left wing, and left engine. The aircraft was subsequently written off as a result of the damage sustained.

4 November 2025 (UPS N529UP)

United Parcel Service (UPS) flight 2976, operated N259UP, was destroyed after it impacted the ground shortly after take-off from Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport (SDF). The three crew members aboard the aircraft and 11 people on the ground were fatally injured. There were 23 others on the ground who were also hurt.

According to video footage, eyewitness reports, and the preliminary NTSB report, during the take-off roll, the left main engine detached from the aircraft, rising upwards and causing damage to the tail-mounted engine.

With the left wing on fire and a major loss of power from engine no.2, the aircraft lifted off but immediately entered a roll to its left side. The aircraft struck the ground with an excessive bank angle and was destroyed by fire.

The NTSB has begun a major investigation into the cause of the crash, with all remaining MD-11s and DC-10s grounded until the report’s findings have been published and recommendations are made.

Will the MD-11 ever fly again?

With a less-than-perfect safety record, the MD-11 may have taken its final flight after the FAA grounded the type following the fatal UPS crash in Louisville. The directive halted all MD-11 and DC-10 operations while the NTSB carries out its investigation and Boeing (which took over the MD-11 programme when it merged with McDonnell Douglas) works on inspection criteria for the type.

According to Boeing sources, these inspection criteria will not be ready before 2026 at the earliest. In the meantime, Western Global Airlines has been hit hardest, with all 15 of its MD-11s now parked with crews furloughed, and with its four 747s still flying. UPS and FedEx have both managed to shift cargo flights to their other aircraft, including Boeing 777s and 767s, as the companies attempt to navigate the peak season demand with a major widebody gap in their fleets.

In the longer term, the grounding will force the remaining MD-11 operators to weigh up the potentially costly structural work required by Boeing and the FAA against retiring a design that is more than 30 years old in any event.

Even if some airframes return, they are unlikely to resume the daily backbone flights that once defined US express parcels operations. To that end, the last true MD-11 revenue-earning flight may already be behind us.

Featured image: Markus Mainka / stock.adobe.com