Study: Scrapping business class seats could drive major cuts in airline carbon emissions

January 8, 2026

Research from Sweden’s Linnaeus University suggests that operating near-full, economy-only seating, combined with efficient airframes, could halve CO2 emissions.

Frequently described as one of the most carbon-intensive activities, aviation accounts for 2.5% of global CO2 emissions, but has contributed around 4% to global warming to date.

Commercial airlines burned the equivalent of 892-936 million tonnes of CO2 in 2019, and without intervention, this figure is projected to rise as air travel demand grows.

How are aviation carbon emissions calculated?

According to Hannah Ritchie, deputy editor and science outreach lead at Our World in Data, aviation’s carbon emissions are determined using three factors:

First is aviation demand, which measures the total volume of passengers and freight movement, in passenger-kilometres and tonne-kilometres.

Second is energy efficiency, which reflects how much energy an aircraft uses per kilometre.

Third is carbon intensity, which depends on the type of fuel being used to determine the carbon emitted per unit of energy. When these three metrics are multiplied, the result is the total carbon dioxide emissions generated by aviation.

Airline efficiency could halve aviation CO2 emissions

In the study published by Communications Earth & Environment, researchers highlight that policymakers, airlines and other stakeholders need to think beyond alternative fuels and new technologies to reduce aviation’s CO2 emissions. They should also rethink how aircraft are configured and operated.

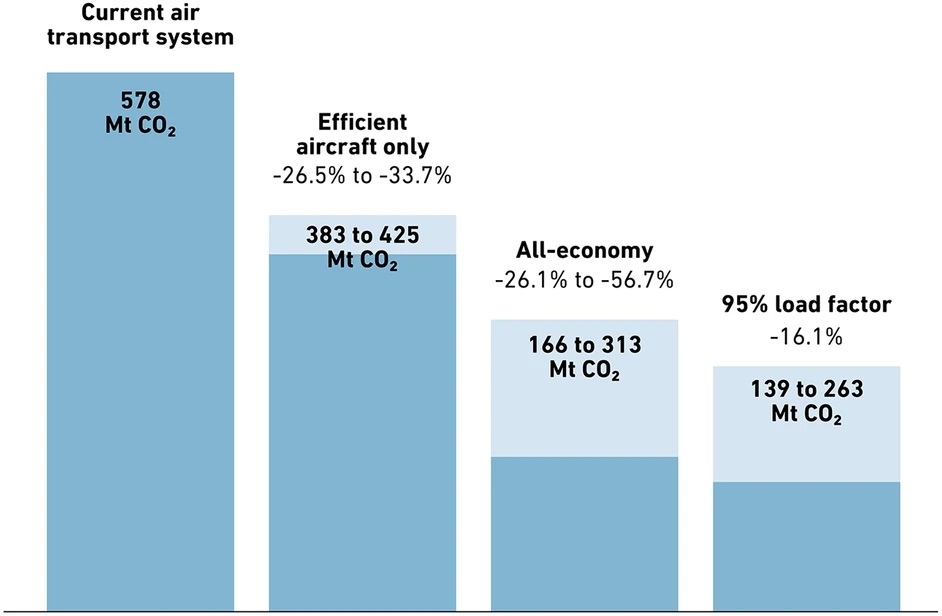

The report led by Prof. Stefan Gössling at Linnaeus University found that operating flights with only economy-class seating on efficient aircraft with optimum load factors could theoretically reduce commercial aviation’s CO2 emissions by nearly 50% compared with current practices.

Commenting on the study, Gössling said: “We found that at least 50% (and up to 75%) of current fuel use could be avoided if airlines were forced to operate at maximum efficiency, while still transporting the same number of passengers over the same distances.”

He also argued that while much of the focus to reduce CO2 emissions has been on sustainable fuels, producing SAF is an expensive and uncertain process with a “significant business risk.” Instead, “It is far more prudent to reduce fuel use,” he said.

Carbon-intensive city pairs and airports

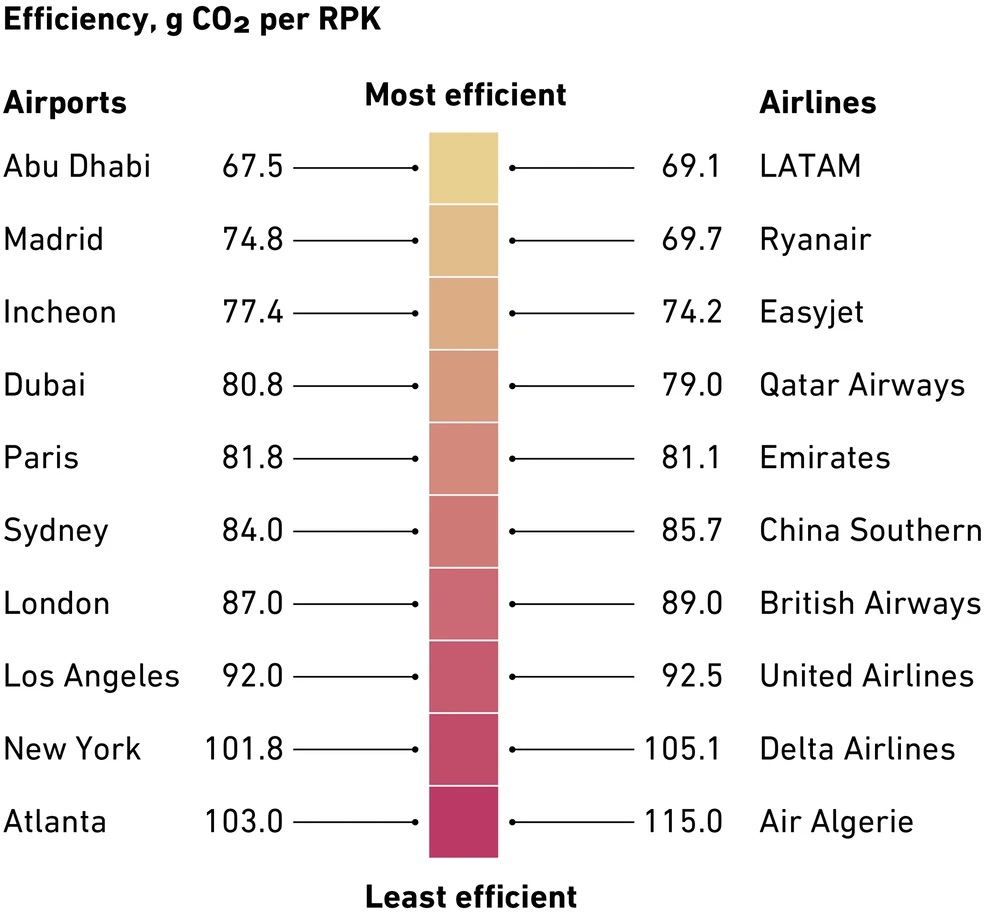

Gössling and his fellow researchers analysed data on 27.5 million flights between 26,156 city pairs in 2023 to understand the variations in CO2 emissions per passenger. The results showed that efficiency differs by region.

Flights departing from airports in the US, Australia and parts of Africa were found to be the most polluting. Atlanta and New York were among the airports with the least efficient flights overall. The study also found that the US – the largest emitting country in the world – had over 14% more polluting flights than the global average.

Airports in India, Brazil and Southeast Asia were primarily served by less polluting flights.

Typically, larger airports have a higher efficiency averaged across arriving and departing flights, while smaller airports that often serve less busy flights have a lower efficiency rating.

Crucially, the report highlighted that operating all routes at their demonstrated optimum could cut emissions by 10.7%. The theoretical 50% reduction is possible with all-economy layouts on the most efficient aircraft and 95% load factors.

Key efficiency measures for reducing CO2 emissions of airlines

- Phasing out inefficient aircraft models (27% to 34% efficiency gain)

- (Plus) removing premium-class seating (total 46% to 71% efficiency gain)

- (Plus) increasing load factors (55% to 76% efficiency gain)

Why economy-only seating matters for airline carbon emissions

While factors influencing fuel consumption and the wider adoption of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are well documented, variations in operational efficiency across global markets have received far less attention.

In response, the Linnaeus University study explores not only the total fuel burned but also how that fuel translates into emissions per revenue passenger-kilometre (RPK) – or the amount of CO2 emitted to carry one paying passenger per km.

Researchers also found that modern aircraft vary widely in their CO2 intensity. The most efficient route (31.6g CO2/RPK) was from Milan in Italy to Incheon Airport in South Korea, while the least efficient (888.3g CO2/ RPK) was between two destinations – Kavieng and Tokua Laukunai, in Papua New Guinea.

It’s no great surprise that newer, lighter and more aerodynamic aircraft will burn significantly less fuel per passenger than their older counterparts. However, the seating layout and passenger load matter because emissions are spread over more people.

Premium seating takes up more space per passenger but generates roughly the same emissions as economy seats for the same flight distance. Configuring an aircraft with all-economy layouts increases the number of seats filled and spreads the emissions more thinly.

The International Air Transportation Association (IATA) reiterates this. It suggests that business and first-class seats are up to five times more CO2-intensive than economy class seats.

The report also highlighted that beyond seating, procedural and more efficient routing also contribute to additional gains. When implemented at scale across airline networks and regions, it’s this ecosystem of operational improvements combined that underpins the theoretical halving of emissions.

Real-world challenges and trade-offs

While the report’s theoretical reduction in CO2 emissions is compelling, significant practical challenges remain.

Passenger preferences continue to influence both seating choices and airline selection. Many travellers value the space, comfort and discretion offered in premium cabins. There is also the risk that previously premium passengers will switch to business jets, which would only further increase the global emissions per passenger-kilometre.

For airlines, these higher-yield products are also integral to commercial strategies, subsidising economy fares and supporting route viability.

What’s more, achieving 95% load factors or at least close to it and all-economy configurations could require policy incentives or restrictions, as well as higher chargers.

Gossling argues that “while strong resistance can be expected, the trade-off is essentially a temporary reduction in personal comfort for a minority of passengers in exchange for avoiding around half a gigatonne of CO2 emissions (in addition to non-CO2 effects).” In fuel terms, this would be equivalent to eliminating the need for approximately 150Mt of SAF.”

Ultimately, the study underlines that meaningful CO2 emission reductions do not rely solely on innovative fuel technology and new aircraft. Changes in how aircraft are configured and operated could also deliver substantial gains. It also reinforces that emissions per passenger are shaped as much by how we fly as what we fly.

Featured image: British Airways