What do the UK’s new drone rules mean for airports?

February 15, 2026

Airports are among the most sensitive environments for drone activity. Just one unauthorised drone can bring about runway closures, flight delays and emergency responses, disrupting thousands of passengers within minutes.

The Gatwick Airport incident in 2018 showed how severe the impact can be, but smaller incursions continue to pose real operational risks across the UK.

Because airport airspace is so tightly controlled, any drone activity near runways, approach paths, or airport boundaries is a major concern.

Preventing disruption, protecting aircraft during critical phases of flight and quickly identifying rogue operators are central to aviation safety. It’s with this in mind that the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) introduced a new drone regulatory framework, which came into force on the 1 January 2026.

Improving accountability after airport drone incidents

One of the biggest challenges airports face during drone incidents is finding out who was responsible. The updated Flyer ID and Operator ID requirements are designed to improve accountability.

Anyone flying a drone weighing 100 grams or more must now hold a Flyer ID, which they can get by passing a free online theory test. This lower threshold brings more drone users into the regulatory system, increasing awareness of airspace restrictions around airports.

Drone owners also now need to register for an Operator ID if their drone weighs 250 grams or more, or if it weighs 100 grams or more and has a camera.

Applicants must be 18 or over, with parents or guardians registering on behalf of younger owners. For airports, this creates a clearer ownership trail following incidents, supporting enforcement and deterrence.

How can remote ID improve safety near airports?

Remote ID is one of the most significant changes for airport safety. Acting like a digital number plate, it broadcasts a drone’s identification and location while in flight.

For airports, this technology reduces uncertainty during drone sightings. Being able to distinguish between authorised and rogue drones near controlled airspace can help authorities make faster, more proportionate decisions, potentially reducing unnecessary runway closures.

Drones with UK class marks must also now use Remote ID. Older “legacy” drones with cameras weighing over 100 grams have until 1 January 2028 to comply. While this improves long-term traceability near airports, the phased rollout means some traceability gaps will remain in the short term.

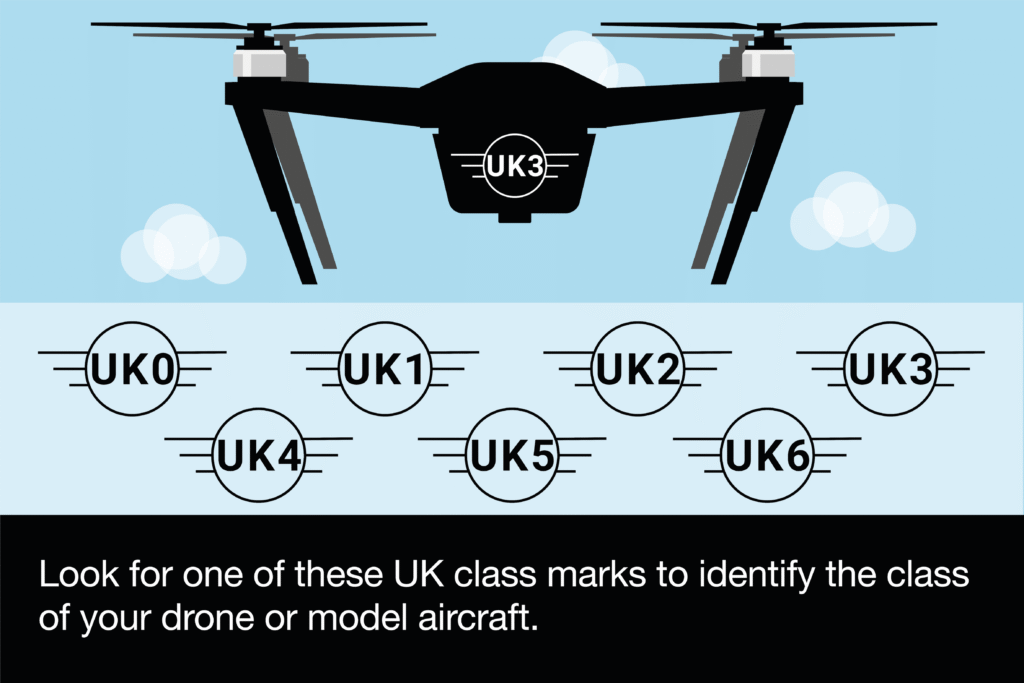

UK class marks and managing risk around airports

UK class marks (UK0-UK6) show a drone’s safety features and determine where and how it can be flown. For airports, these classifications help regulators better understand what types of drones may legally operate near different airspace categories.

All new drones sold in the UK must carry a UK class mark from 2026. Drones bought before 2026, or those with EU class marks, can continue flying under transitional arrangements until the end of 2027.

This avoids grounding large numbers of drones, but it does leave airports managing a mix of older and newer drones with different compliance requirements.

Night flying and visibility risks

Night flying already presents higher risks for aviation, as aircraft crews rely on predictable lighting and reduced visibility makes unexpected objects harder to see.

Under the new rules, any drone flown at night must carry a flashing green light that remains visible throughout the flight, with the light’s weight counting toward the drone’s total mass.

For airports, this improves the chances of spotting unauthorised night flights and reduces collision and near-miss risks.

Flight restriction zones and enforcement challenges

Flying inside FRZs without permission from the airport and the CAA is illegal – but the challenge is in enforcement. With complicated boundaries, neighbouring residential areas and a lack of awareness of the rules, airports can’t rely on regulation alone. They still need strong detection systems, police coordination and quick response measures.

What the new drone rules deliver and where there are still gaps

The new regulations are meant to improve safety, make drone operators more accountable, raise standards through testing and registration and reassure the public that aviation is being properly protected.

Airports benefit from stronger legal support and better identification tools, which should cut down both the number and length of drone-related disruptions.

However, enforcement isn’t perfect yet. The Remote ID transition leaves some gaps, and overseas operators now have to navigate a more complicated UK-specific system.

The rules are still very new. They’re a step in the right direction, but how effective they really are will only show when they’re put to the test.

Featured image: A2RL