2 years on: JTSB publishes 2nd report on Japan Airlines-Japan Coast Guard 2024 Haneda Airport runway collision

December 29, 2025

Japan’s Transport Safety Board (JTSB) has published a second progress report in its investigation into the January 2, 2024, runway collision at Tokyo Haneda International Airport, which involved a Japan Coast Guard Bombardier DHC-8-315 (JA722A) and a Japan Airlines Airbus A350-941 (JA13XJ).

On 25 December 2024, the JTSB released an interim report detailing its ongoing investigation after determining that the factors involved in the incident could not be adequately studied in a year. The latest progress report outlines additional analysis and verification work—most notably a night, no-moonlight visibility simulation conducted this past March, designed to better understand why the landing crew did not detect the Coast Guard aircraft on the runway until moments before impact.

The crash remains one of the most serious aviation accidents in Japan in recent years. Investigators have conducted an in-depth analysis of human factors, air traffic control procedures, and safety systems to identify causal factors for the incident.

What happened: Sequence of events in the 2024 Haneda runway collision

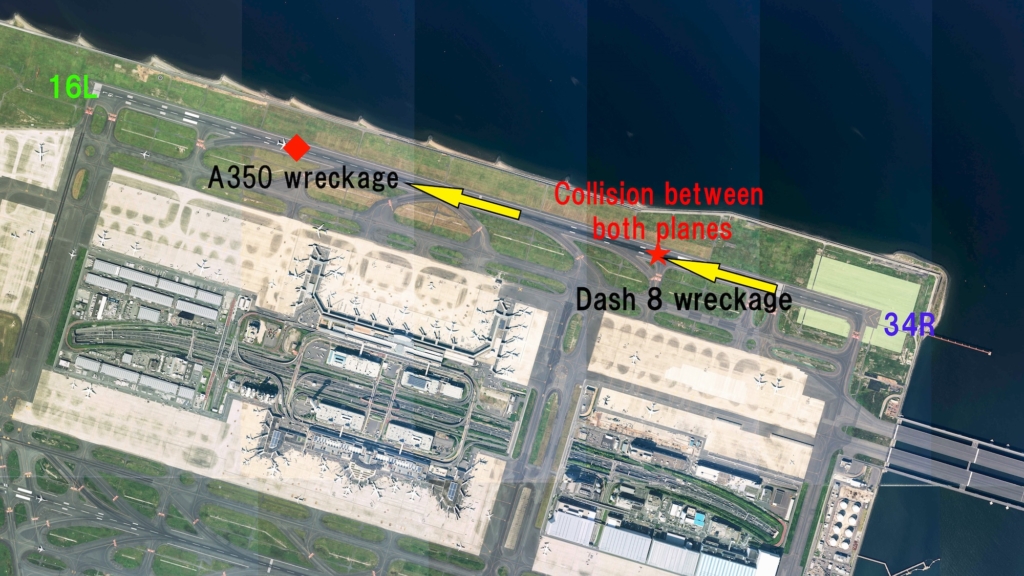

- On 2 January 2024, Japan Airlines Flight 516 (an Airbus A350) was landing on runway 34R at Haneda Airport in Tokyo after a domestic flight.

- Simultaneously, a Japan Coast Guard Dash-8 aircraft (JA722A) was taxiing to the same runway in preparation for departure while supporting post-earthquake relief operations.

- The Dash-8 entered the active runway without proper clearance, a critical error that culminated in a collision with the landing A350.

- Both aircraft were destroyed by fire upon impact. The Dash-8 burst into flame upon colliding with the A350. The A350 fuselage was also set on fire, but it progressed more slowly, allowing time for an evacuation as soon as the aircraft came to a stop.

- With a quick response to the emergency by the crew and passengers, all 379 people on board the JAL flight survived. One passenger suffered serious injuries during the evacuation, four suffered minor injuries, and twelve others received medical attention after feeling unwell. Unfortunately, five of the six Coast Guard crew members perished in the fire.

Key JTSB findings on the Japan Airlines-Japan Coast Guard crash

In the interim report published at the end of last year, the JTSB identified three key factors that led to the crash.

1. Human error leading to a runway incursion

The interim report finds that the Coast Guard flight crew mistakenly believed they had authorisation to enter the runway due to a misunderstanding of clearances between the aircraft and air traffic control.

After the Japan Airlines Airbus A350 received clearance from Tower East to land on Runway 34R, the control for the Japan Coast Guard Dash 8 was transferred to Tower East. Tower East instructed the Coast Guard to taxi to the runway holding position on Taxiway C5.

The tower informed the Coast Guard pilots that the takeoff order was number one. They understood the instruction to mean that Tower East had granted it priority for takeoff over other aircraft and had been cleared to enter the runway. The crew entered the runway and stopped there.

However, Tower East did not realise that the Coast Guard aircraft had entered the runway and remained there. The Japan Airlines A350 was also unaware that the Coast Guard aircraft was on the runway and continued its landing approach, colliding with the Dash 8 immediately after touchdown.

2. Air traffic control awareness and monitoring failures at Haneda Tower

Despite normal radar and ground surveillance systems, air traffic controllers did not detect the unauthorised runway entry in time to alert either aircraft or to stop the landing sequence, indicating potential procedural and situational awareness gaps.

During the incident, Tower East was managing multiple aircraft and was distracted by inquiries from the Tokyo Radar Approach Control Facility. This distraction resulted in the Coast Guard aircraft entering the runway without clearance when the Japan Airlines A350 was expected to land.

3. Monitoring and alert systems

Despite a warning issued by the airport’s Runway Occupancy Monitoring Support System that two aircraft were present, Tower East failed to recognise the alert. The system warnings were visual only, not audible, which might have drawn ATC’s attention and potentially avoided the collision.

Safety implications of the Haneda runway collision

The accident drew attention to the risks of runway incursions. The investigation so far points to the need for enhanced surveillance tools, clearer ATC procedures, and improved human-machine interfaces for ground movement monitoring.

The JAL A350 loss also prompted reviews of evacuation procedures and training. The fire had disabled five of the aircraft’s eight emergency exits. The crew was only able to safely deploy three slides: two at the front of the aircraft and one at the back. That all passengers survived with relatively few serious injuries is a notable safety outcome. It is attributed to the crew’s rapid response and passengers’ cooperation with instructions to exit the aircraft quickly.

JTSB investigation shifts focus to preventing another Haneda runway collision

The JTSB has continued its investigation and analysis since then with a focus on recurrence prevention and damage mitigation. The board stated it issued this second update ahead of the two-year mark because the accident involved a scheduled passenger service and remains a matter of high public interest.

In the second report, JTSB says it continues to examine the same three broad “factor” areas outlined previously—Coast Guard aircraft actions, air traffic control, and the JAL aircraft—and adds several new, more granular human-factors and systems questions.

1) Coast Guard Dash-8 crew factors: fatigue, training gaps, and checklist discipline

Building on its earlier conclusion that the Coast Guard aircraft entered and stopped on the runway, believing it had clearance, JTSB says it is now analysing additional potential influences on the captain’s recognition and decision-making. These include fatigue and duty management, as well as the fact that the captain had not flown that aircraft type in the 30 days prior.

The JTSB is also investigating a procedural anomaly in which the first officer correctly read back ATC instructions, yet the captain began a Before Takeoff Checklist, typically performed after runway entry clearance.

The board also flags the absence of a sterile cockpit rule at the Coast Guard’s Haneda base and the possibility that the crew did not mutually confirm there were no aircraft on final approach before entering the runway. The “sterile cockpit rule” would prevent conduct (like non-essential conversation) that might interfere with crew concentration on safety-related duties during critical phases such as takeoff and landing.

2) ATC oversight at Haneda: monitoring roles, alerts, and safety management gaps

For the tower side, JTSB reiterates that Haneda ATC did not recognise that the Coast Guard aircraft had entered and was stopped on the runway, and says it is now digging deeper into how continuous monitoring was executed and what support functions were available.

Notably, the report highlights that the tower’s flight surveillance position was, as a rule, tasked with monitoring aircraft movements related to a different runway, and was not assigned to monitor movements on Runway C (34R)—a workload/design choice the board is now focused on analysing further.

JTSB also points to the Civil Aviation Bureau’s safety management system and whether it effectively supports introduction, evaluation, improvement, and frontline feedback for runway occupancy monitoring support functions.

In a cross-reference, JTSB notes parallels with how CNF (close approach warning) operated during a prior accident between two Japan Airlines aircraft—Flight 907, a Boeing 747-446D registered JA8904, and Flight 958, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-40 registered JA8546.

On January 31, 2001, the aircraft came into extremely close proximity over the Pacific Ocean near Yaizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture. As reported by Aviation Safety Network, the two aircraft were cruising at similar flight levels and on intersecting paths when a controlled flight conflict developed.

Although the aircraft did not collide, they passed within approximately 135 metres (443 feet) of each other—a very close vertical and lateral separation that triggered a TCAS (Traffic Collision Avoidance System) resolution advisory and required abrupt avoidance manoeuvres by both flight crews. The JTSB is now using that historical case to frame questions about procedures, training, and what happens when alerts do not operate as expected in the context of the 2024 crash.

3) Japan Airlines A350 HUD use and the “why didn’t they see it?” question

On the JAL A350 side, JTSB continues to analyse why the flight crew did not recognise the Japan Coast Guard aircraft on the runway until immediately before impact.

In addition to visibility at night from the approach path, the report says investigators are examining whether the fact that both pilots were using the Head-Up Display (HUD) affected their external monitoring during the landing phase.

JTSB night visibility simulation recreates Haneda runway conditions

The investigation’s most notable new element is a visibility verification experiment conducted March 26–27, 2025, designed to study the crew’s view on a night without moonlight, replicating conditions during the accident. JTSB placed a DHC-8-315 of the same type as the Coast Guard aircraft on a runway at Chubu Centrair International Airport. This airport was selected because it is comparable in runway lighting configuration to Haneda’s Runway 34R, but has less night traffic for safer controlled testing.

Investigators captured imagery from the air using a small fixed-wing aircraft and a helicopter, with airport lighting set to match the accident’s brightness settings, and external aircraft lighting configured as it was during the accident.

Because the Coast Guard aircraft’s rearward-visible external lights were white and the surrounding runway centerline and touchdown-zone lights were also white, JTSB additionally tested visibility when the aircraft’s external light colour was changed to red, and when the aircraft’s position was offset from the runway centerline lights, to evaluate whether contrast and alignment with lighting patterns affected detectability.

Damage mitigation analysis: evacuation communication, smoke, and survivability

Beyond causal factors, the second progress report also expands JTSB’s work on damage mitigation—how systems and procedures influenced survivability and evacuation outcomes.

JTSB reports it conducted a May 26, 2025, verification experiment aboard an A350-941 to test the use of the aircraft’s loudhailer (megaphone) in a scenario where the cabin PA system was not functioning, as was the case during the crash. The test measured sound levels at multiple cabin locations and collected subjective evaluations under simulated acoustic conditions, including engine noise and an evacuation/panic-control environment.

It is also conducting component analysis of smoke and odours generated in the cabin after the fire, noting that smoke increased in density over time and reduced visibility inside the aircraft during evacuation—making audio communication especially critical.

Tower visibility checks and international coordination in the Haneda investigation

JTSB says it repeated on-site confirmation from the Haneda control tower on September 19, 2025, building on earlier checks, to assess how aircraft and lights appear from the tower at night in light of evolving analysis.

The board also convened a three-day information exchange meeting on September 9–11, 2025, with investigators from states involved in aircraft and engine design and manufacture, including Canada, France, the UK, Germany, and the US, to share investigation status and discuss analysis of verification experiments.

JTSB states it will continue factual verification and analysis toward a final report, including holding opinion-hearing sessions, gathering views from relevant parties, and consulting related states, to determine both the accident’s causes and the causes of resulting damage, then identifying concrete recurrence-prevention and damage-mitigation measures.

Featured Image: Makochan12.9 | Wikimedia Commons