Engine maintenance: How jet engines keep flying for so long

December 26, 2025

Aircraft engines are complex machines that require immaculate care and routine maintenance. An engine requires a maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) shop visit based on the number of engine flight hours (EFH) or engine flight cycles (EFC).

An EFC is defined as engine start-up, heating to operating temperatures, and shut-off. In other words, a typical flight between point A and point B would incur one EFC.

Narrowbody versus widebody engines

Narrowbody aircraft accumulate anywhere between 2 and 4 hours per EFC. Widebody aircraft, on the other hand, typically fly for 6 to 8 hours per EFC. The ratio of EFH to EFC would generally determine the need for an engine shop visit.

Depending on the size, type, and thrust rating of an engine, a maintenance shop visit is required. The time between overhauls (TBO) for modern narrowbody engines is between 7,000 and 15,000 EFC. Moreover, life-limited parts (LLP) installed on engines may have a lifespan of 5,000 to 30,000 EFC, depending on the LLP group.

For example, the CFM56-7B engine powering the Boeing 737 NG aircraft has various LLP groups with varying limits – the hot section has a limit of 20,000 EFC, the compressor section at 25,000 EFC, and the relatively cooler low-pressure system has a 30,000 EFC limit.

The International Aero Engines (IAE) V2500 powering the Airbus A230ceo family aircraft employs a single uniform LLP limit for all modules – 20,000 EFC.

An overhaul shop visit for widebody aircraft is generally determined based on the EFH incurred. On average, a widebody engine is due for an overhaul at approximately 20,000 EFH. The lifespan of LLPs on widebody engines, such as the General Electric GE-90, ranges between 3,500 EFC and 20,000 EFC, depending on the component group.

Irrespective of the engine’s type and size, operators may choose to align the engine’s first shop visit with the LLP limit of the lowest component group. Apart from LLP replacement, OEMs and MRO centers aim to restore engine performance, typically measured by its Exhaust Gas Temperature (EGT) Margin. It is the difference between the operating EGT and the red-limit EGT specified by the manufacturer

An overview of engine maintenance philosophies

Aircraft engine maintenance philosophy can be broken into two categories: preventive maintenance and on-condition maintenance. Preventive maintenance, a rather old-school strategy, ensures that the aircraft always operates in a top-notch condition. As such, frequent inspections, repairs, and replacement of parts are conducted.

Timed inspections of all critical and non-critical components, systems, and modules are carried out to prevent mechanical failure. In doing so, functional parts and systems can be immaturely repaired or replaced. While a significantly proactive approach, preventive maintenance is time-consuming and costly.

In contrast, on-condition maintenance relies on data and triggers from condition monitoring systems that detect faults and potential failures. Depending on the system’s criticality, predictive alerts and notifications drive engine maintenance. Darren Macer, a senior technical fellow at Boeing Global Services, emphasises the importance of predictive maintenance by stating,

“Data has become the lifeblood of the aerospace industry. We strive to enhance aircraft systems and components to provide more sensor data, enabling analysis that supports increasingly accurate and valuable insights on the aircraft’s operational performance.”

“The focus has led to a growing emphasis on evaluating predictive model performance, specifically prediction accuracy and the actions taken from alerts. This focus is reshaping feedback loop data sharing for predictive models, necessitating collaboration among airlines, OEMs, suppliers, MROs, and parts providers to achieve greater success.”

The maintenance is based on the defect and serviceable limits of the part. Specific inspection and repair work scopes are defined to prevent over-inspection and maintenance of functional parts.

What happens during a maintenance shop visit

Aircraft engines undergo extreme structural and thermal stresses during operation. Varying climate conditions that aircraft fly in only add to the physical wear on jet engines. Aircraft maintenance begins with incoming inspections and preparation of a detailed workscope outlining maintenance levels and criteria.

Induction and preliminary inspections

The unserviceable engine is inducted into the shop, washed, and inspected to identify its incoming condition. Highly sophisticated borescope inspection (BSI) is performed through the use of a flexible tube with a camera and light.

Live video of hard-to-reach internal components of the engine is recorded to assess internal condition, diagnose problems, and determine the scope of maintenance. External components, including accessories, are visually inspected to identify missing or damaged components.

Preparing a tailored workscope for the job

Maintenance workscopes are prepared based on customer requirements and the existing condition of the engine. These range from a fairly simple LLP replacement workscope to a more detailed performance restoration.

The maintenance workscope drives how much or how little disassembly is required. It is common for the work scope to be upgraded multiple times during the job as more inspections are conducted. Multiple upgrades are particularly true for investigation engines, such as for bird strikes, flame-out events, etc.

Engine disassembly

The engine is disassembled based on the maintenance workscope. A minimal workscope may only require disassembly at a modular level (generally into low-pressure, high-pressure, and turbine modules).

Conversely, a comprehensive workscope level may require the engine to be disassembled at the piece part level – requiring individual parts (including internal airfoils) to be disassembled and inspected.

Repair and replacement

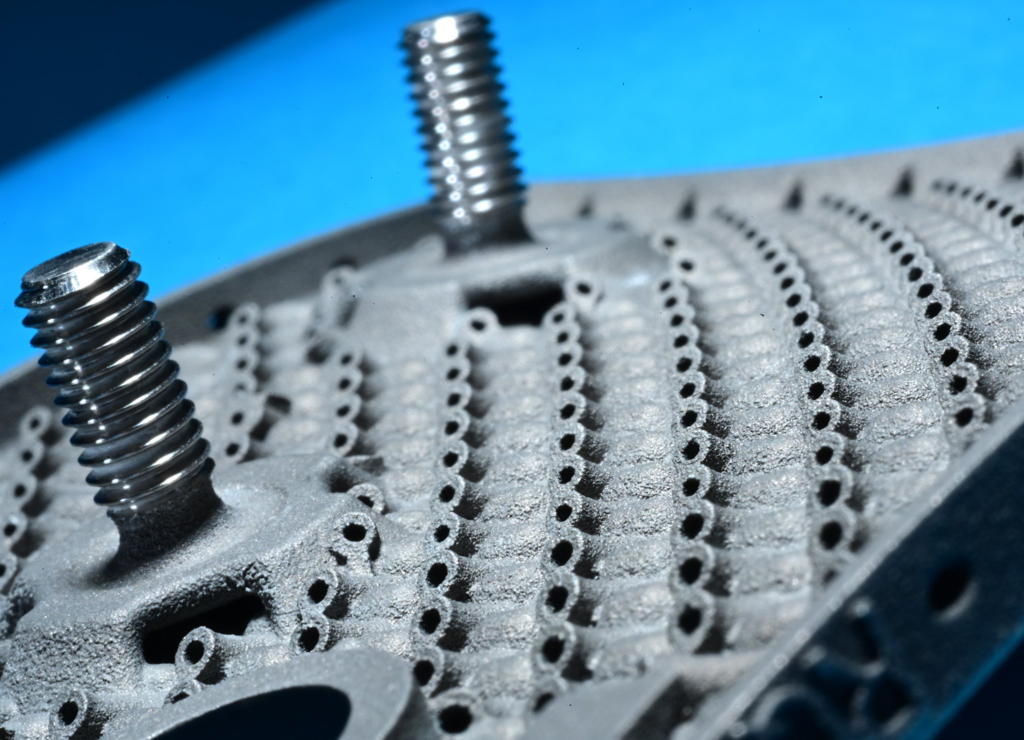

Disassembled parts are individually inspected and sent for repair where applicable. Parts with no repairs or those beyond repairable limits are replaced with new or used (aftermarket) serviceable ones. Logistics and supply chain teams ensure that new or used parts are acquired with all necessary and traceable paperwork.

Any repairs performed on aviation parts must be in accordance with the engine manual or other documents released and certified by the OEM. After the required repair is completed, the repair centre must provide a serviceability (airworthiness) certificate.

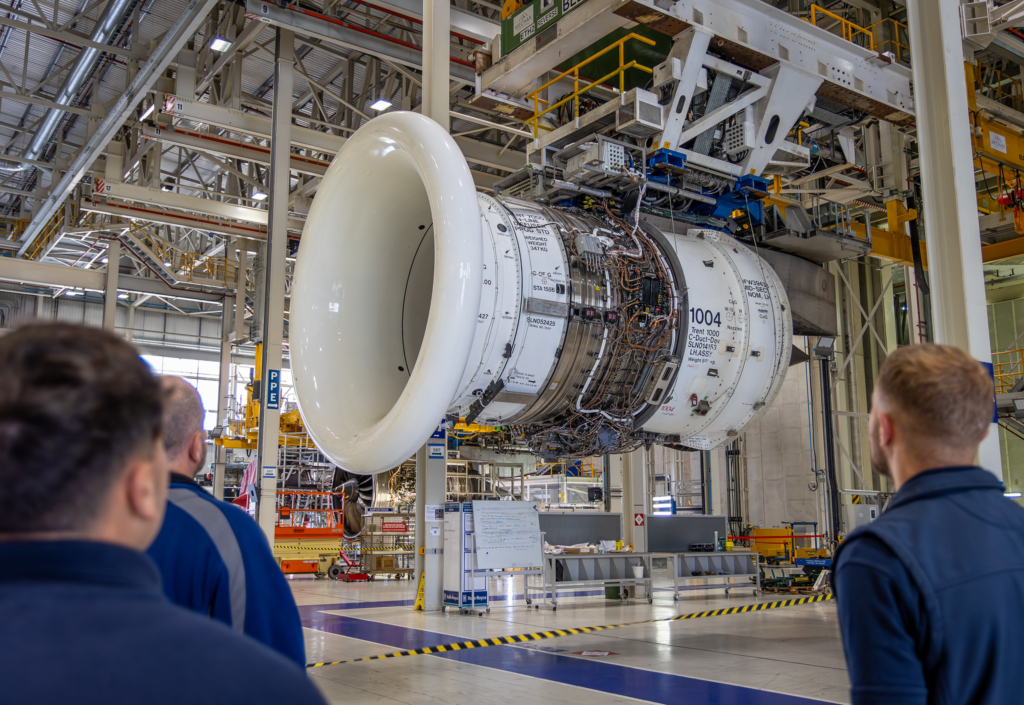

Engine build and testing

New, used, and repaired parts come together during the build phase – the last step before the engine can be tested under operating conditions. Individual parts are assembled within modules, which then proceed to the final build. At this point, all individual components on the engine are serviceable, but the engine itself is not.

In a specially-designed facility (test centre), the engine is run at operating conditions. A range of performance parameters, including the EGT Margin, is measured for serviceability. A final airworthiness certificate is issued before the engine makes its way to the customer. The serviceable engine is installed on the wing with the CSLSV (cycles since last shop visit) set to zero.

Featured image: Rolls-Royce