The four-stroke cycle of an internal combustion engine, “suck, squeeze, bang, blow”, is often used to describe the function of a jet engine. The cycle, representing air intake, compression, power, and exhaust, describes the operation of an automobile piston engine where air and fuel are drawn into a cylinder.

While jet engines work on the same principle, they don’t actually suck air into the inlet. Instead, jet engines reshape the atmosphere around the inlet, thereby precisely creating a pressure difference.

When large fan blades spin at high speed, a low-pressure zone is created at the inlet, in front of the fan. It causes the high-pressure atmospheric air to rush in to fill the void.

| The four-stroke cycle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Suck | Squeeze | Bang | Blow |

| Air intake – The movement of the piston opens the intake valve to draw fuel-air mixture into the cylinder. | Compression – The rising of the piston compresses the fuel-air mixture into a high-pressure, high-temperature volume. | Power – Ignition of the compressed mixture happens, forcing the piston down and turning the crankshaft | Exhaust – The piston rises again, pushing the combusted gases out of the cylinder through the exhaust valve |

In pure physics terms, it is considered a pressure differential that allows atmospheric air to flow into the engine inlet. The engine inlet is designed to allow smooth, steady, and continuous airflow into the engine, even at high angles of attack. Moreover, the shape of the inlet cowling prevents the incoming airflow from becoming turbulent.

What happens after the atmospheric air has entered the engine

The engine fan blades are precisely engineered to manipulate the surrounding pressure, allowing large amounts of air into the engine. The air is split into two streams: a core flow and a bypass flow. A small portion (approximately 10-20%) of the air is directed to the engine core for combustion. The majority of the air (approximately 80-90%) is guided around the core through a bypass duct, contributing to the engine thrust.

The air in the core flow passes through a series of compressor stages, each comprising rotating blades (rotor) and stationary vanes (stator). The primary function of the rotor is to accelerate the air, increasing its velocity and tangential speed (swirl). Moreover, it increases the total pressure of the air while pushing it aft towards the next stage.

The stators are fixed airfoils mounted to the engine casing, slowing high-velocity air from the rotor. As a result, the static pressure of the air increases. Stator vanes also straighten the “swirling” airflow from the rotor, optimising it for the next stage.

Since a single stage is not sufficient to produce optimal pressure, modern jet engines feature multiple, alternating stages. The design enhances the overall pressure ratio required for efficient combustion. Notably, the compression area decreases along with each stage, allowing the air to be gradually compressed while maintaining constant axial velocity.

Optimal conditioning of air and fuel ensures efficient combustion

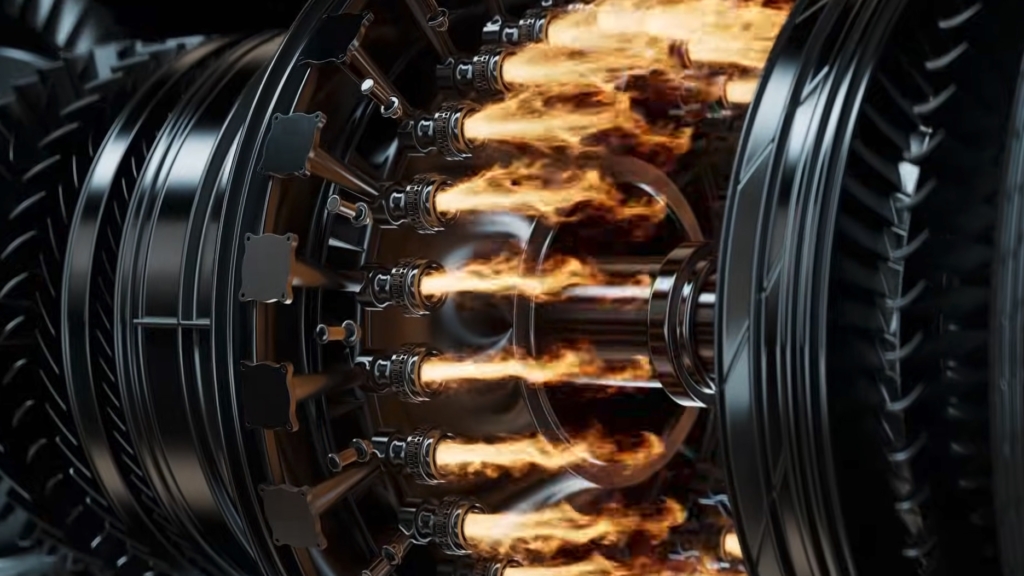

In addition to the optimally compressed air, fuel is also compressed and heated for combustion. Efficient combustion is achieved through precise mixing of air and fuel in a pressure and temperature-controlled environment with active cooling.

Fuel nozzles atomise liquid fuel into a fine mist, increasing the surface area and allowing rapid mixing with air. Controlled ignition of atomised fuel-air mixture maximises thermal efficiency while ensuring that combustion gases are hot enough to efficiently drive the turbines.

The energy transferred to the low-pressure (LP) turbine spins the fan, creating a continuous pressure differential for the atmospheric air to be drawn into the engine.

Featured image: Julian Herzog / Wikimedia Commons