A 3D-printed aircraft? Saab reveals world-first fuselage built entirely by AI and additive manufacturing

December 11, 2025

Saab has unveiled a world-first in aerospace manufacturing: a five-metre aircraft fuselage that has been entirely 3D-printed using Divergent Technologies’ additive production system and is intended to fly in 2026.

More than a novel structure, the demonstrator represents the first attempt by any airframer to treat physical hardware with the same flexibility and upgrade pace normally associated with software. If flight tests succeed, Saab believes the concept could open the door to a new industrial model in which aircraft can be redesigned, built and iterated almost as quickly as software releases.

The development reflects a broader shift in Swedish aerospace thinking. Saab has long argued that battlefield advantage comes from the ability to observe, orient, decide and act faster than an opponent. That philosophy has influenced everything from the original Gripen’s cost-efficient modular design to today’s digital engineering methods.

The new 3D-printed fuselage is the latest expression of that mindset, bringing together additive manufacturing, AI-driven optimisation and model-based engineering in a single physical structure.

Gripen E’s digital development becomes the foundation for Saab’s 3D-printed fuselage

The groundwork began during the Gripen E programme, where Saab adopted model-based engineering across its aeronautical and vehicle systems teams. Saab says the approach allowed every discipline to work from a shared digital twin of the aircraft, enabling early simulations, faster trade studies and more informed integration choices before manufacturing began.

The transition into production also marked a shift away from paper drawings, replacing them with digital 3D definitions for every part and procedure. This enabled more complex and optimised designs.

Gripen E’s avionics architecture went further, introducing hardware independence and separating flight-critical and mission-critical software. Saab says this broke from long and expensive upgrade cycles, allowing high-speed mission software updates.

It also made Gripen E, according to Saab, “the first in-production fighter to fly with an AI agent on board in standard avionics computers.”

This experience became the foundation for the next question: if software could be changed rapidly, could hardware follow the same principle?

Inside Saab’s software-defined hardware shift using AI and 3D printing

Inside Saab’s Rainforest innovation unit, engineers explored how model-based methods could combine with additive manufacturing to make physical structures as adaptable as digital code.

Axel Baathe, head of Rainforest, said his engineers asked how to provide the same level of flexibility for structures that Gripen E already offers for software.

“We are asking ourselves the question – in Gripen E, customers get a platform where they can code mission-critical applications in the morning and fly them in the afternoon,” Baathe said. “How can we give them the same level of software flexibility, but for actual hardware? We call this Software-Defined Hardware Manufacturing.”

Baathe added that model-based engineering creates high-fidelity simulation models and quickly shows how to improve a design, but manufacturing is usually the bottleneck. Conventional factories depend on tools, moulds and jigs that take time and money to order and calibrate.

“Software-defined manufacturing changes this,” he said. “It brings us the same speed and flexibility that we have during design to our manufacturing.”

Saab and Divergent build a 3D-printed, AI-optimised aircraft fuselage

This pursuit led Saab to Divergent Technologies, whose Divergent Adaptive Production System integrates AI-driven design, laser powder-bed additive manufacturing and fixtureless robotic assembly.

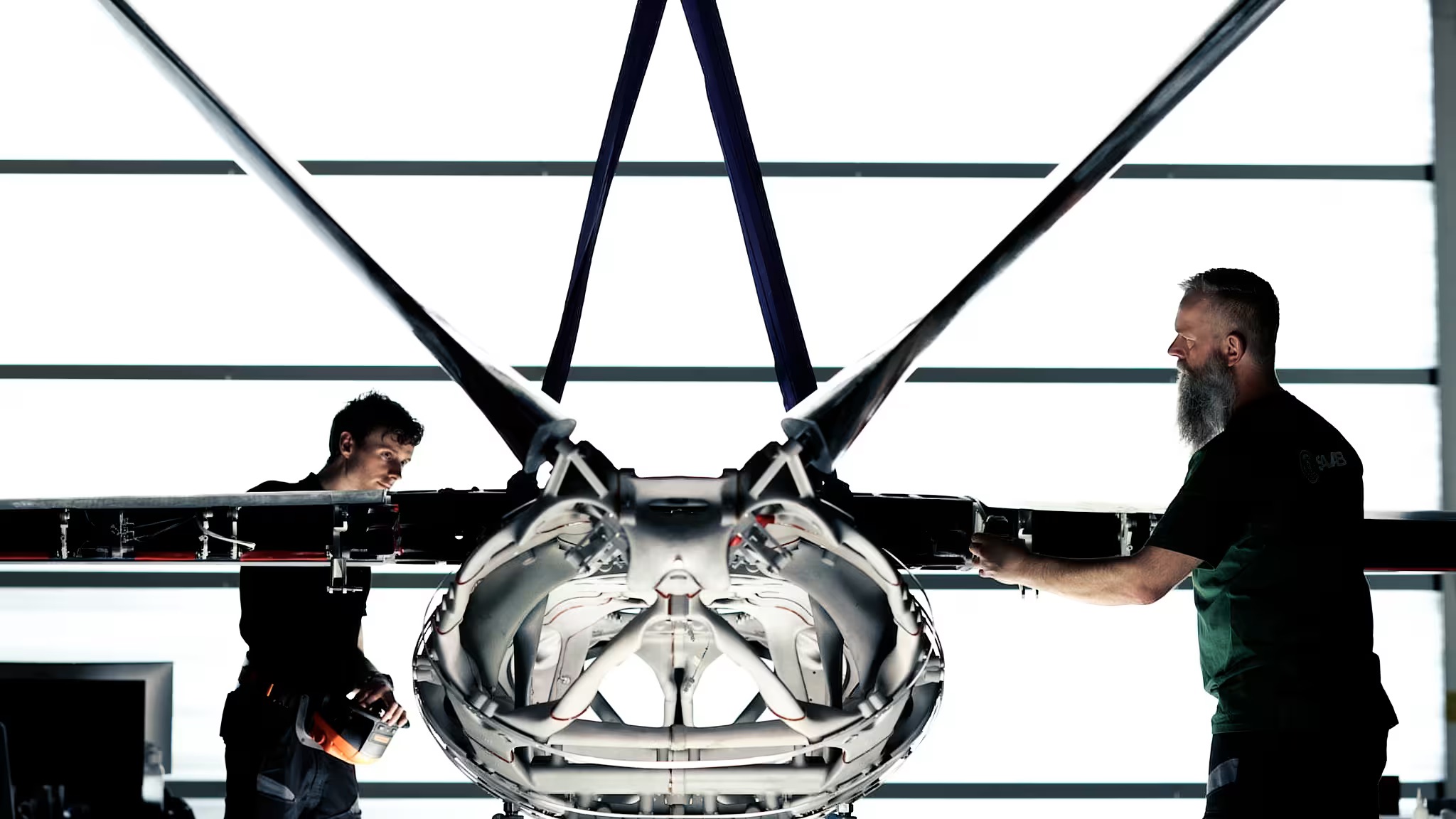

The collaboration has produced a five-metre fuselage section made entirely without unique tooling and using just 26 printed metal parts. It will be among the largest 3D printed structures ever to undergo powered flight.

Saab says many long-standing rules of airframe construction were challenged. Instead of ribs, spars and right-angle stringers, load-bearing structures were shaped organically along optimal load paths generated by design algorithms. “It is impossible to, as a human, draw these parts,” Baathe said. “Instead, they must be generated by optimisation and AI algorithms.”

The printed structure reduces part count by at least a factor of 100 compared with a traditional fuselage and removes the need for thousands of rivets.

Saab and Divergent say the approach also enables flexible weight optimisation and greater functional integration, with systems such as wiring, thermal management channels and even hydraulic routing printed directly into the structure.

The fuselage has passed structural proof loading and is scheduled to fly in 2026 as part of an autonomous airborne platform Saab is developing.

Saab develops a reconfigurable digital factory for next-gen aircraft production

Beyond the structure itself, Saab sees this as the first step towards a broader transformation in production. Baathe says the ambition is a factory that reconfigures itself automatically to match whatever digital twin engineers produce.

“We envision that Saab’s future production factory is our most important product,” he said. “We want to be able to give our customers freedom. Freedom to not feel locked into a specific design, neither in hardware nor software.

“The production factory will be one that reconfigures itself instantly to build whatever our joint digital twin looks like, without being limited by expensive investments in new tooling. We sum this up as ‘CAD in the Morning, Fly in the Afternoon’.”

Such a capability would mark a major shift from today’s aerospace manufacturing model, where factories are built around long-lived tooling for a single aircraft type. Saab acknowledges that this transition will take time and require advances in several production methods, but says the first steps demonstrate what may eventually be possible.

What Saab’s software-defined fuselage means for future fighters and unmanned aircraft

While Saab has not linked the fuselage to any future manned fighter, the implications are clear.

A software-defined hardware approach could enable rapid structural iterations, mission-specific fuselage variants or lightweight unmanned platforms built to order for specific needs. It could also reduce the cost barriers associated with redesign, which often deter mid-life updates and tailored configurations.

Saab says the new approach “reduces the cost of change, making redesign and implementing innovative ideas easier”. If additive structures continue to prove reliable, the model may influence how Sweden and other nations approach future combat air projects in the 2030s and beyond.

Saab’s 2026 test flight could shift certification rules for additive manufacturing

The 2026 flight will not only validate the structure’s strength but may also influence regulators’ approach to major printed structures.

To date, 3D printing in aviation has mostly been confined to brackets and secondary components. Certifying primary printed structures has been slow because of inspection challenges and limited flight data. A successful demonstration of a full fuselage could begin to shift those boundaries.

For Saab, the flight is also a practical benchmark for how quickly physical changes can be made once a design is finalised. The company says lead times are now determined less by tooling and more by the speed of algorithms, printers and assembly robots.

For all the engineering novelty, the underlying driver is strategic. Rapid upgrade cycles are becoming essential in modern airpower. Recent conflicts and the rise of autonomous systems have shown that the ability to iterate quickly can matter as much as raw performance.

Saab positions the new fuselage as an early, visible step in showing how digital design and advanced manufacturing can converge at scale. The company sees it not only as a technological milestone but as a shift in industrial philosophy, one that could allow smaller nations or more constrained defence budgets to field cutting-edge systems without multi-decade investment cycles.

“The joint team has done an excellent job working to prepare for first flight,” Saab said in its announcement.

If the 2026 test flight succeeds, Saab and Divergent may have taken the most significant step yet towards a future in which aircraft are no longer built around fixed shapes and long-term tooling, but around software-defined designs that evolve as quickly as operational needs.