Reverse thrust: Why aircraft engines open when they land

December 24, 2025

You can see it out of the window: the wheels hit the runway, there’s a slight jolt, and suddenly the engine nacelles slide open like mechanical gills. A deeper roar follows, and the aircraft slows down fast. It’s the exact moment the thrust reversers do their thing.

Reverse thrust: Stopping aircraft safely

Modern aircraft engines are built to provide maximum efficiency and power throughout various stages of flight.

Even after touchdown, most jets are still barrelling along at 125-145 knots. The spoilers pop up, the brakes kick in, but for the first few seconds, it’s reverse thrust that gives the biggest helping hand.

They can be used all the way up until a complete stop, but most aircraft in normal operations will stow them at speeds below 60-70 knots.

At high speeds, reversers can provide up to around 40% of the total deceleration effort, buying precious runway and reducing stress on the brakes. They’re also crucial in a rejected takeoff.

Pilots don’t think twice about using them. As soon as the aircraft senses weight on the wheels, the reverse levers unlock. A gentle pull activates “idle reverse” – often enough for a long runway – while a stronger pull calls for full reverse to prevent an overrun.

Why do the engines appear to “open up”?

Those moving panels aren’t for show – they’re the visible part of a remarkably clever bit of engineering.

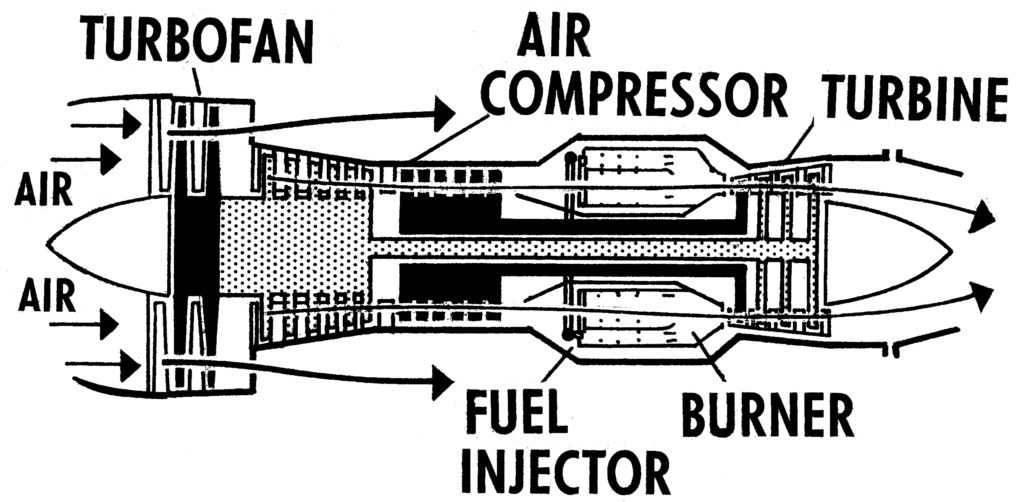

On most jets, the thrust reverser uses a cascade system in which the outer cowl slides backwards to reveal a set of cascade vanes. At the same time, blocker doors pivot into the bypass duct to seal off the normal rearward flow. This forces the cool bypass air to exit through the cascades, creating a forward-directed braking force.

Only the bypass stream is redirected, not the hot engine core exhaust, which is why modern high-bypass engines, with ratios typically between 5:1 and 12:1, are so effective at producing significant reverse thrust without compromising engine integrity.

For reference, the setup on the likes of an ATR is different. Instead of opening panels, the propeller blades simply twist to bite the air in the opposite direction, producing a surprisingly strong braking force – and all without any nacelles moving at all.

The final type of thrust reverser is the clamshell. This consists of a pair of doors at a jet engine’s rear that swing into the exhaust, redirecting thrust forward to help slow the plane. They are mainly found on older turbojet and early low-bypass turbofan aircraft.

Why reverse thrust is important for trickier landings

The UK has its own quirks when it comes to landing: runways that are frequently damp, sometimes relatively short, and often subject to persistent crosswinds.

In these conditions, reverse thrust can shorten landing distances by 300-700 metres, depending on aircraft type (handy when landing at London City Airport with its very short runway, for example).

It also provides extra stopping power when wet surfaces reduce brake effectiveness, whilst keeping the aircraft stable in challenging crosswinds during the initial rollout.

Thrust reversers: Deceleration by design

For most passengers, reverser deployment is just a noisy, slightly dramatic moment between touchdown and taxi. But it’s also an interesting and vital bit of aircraft engineering that makes landings safer, more efficient and more consistent.

When the engines open up during rollout, it’s simply a finely tuned mix of aerodynamics and mechanical design doing one of the most important jobs in the landing sequence – to bring every flight to a controlled, managed stop.

Get all the latest commercial aviation news on AGN here.

Featured image: Adwo / stock.adobe.com