Japan’s new lithium-air battery breakthrough could be a gamechanger for eVTOLs and electric aircraft

November 25, 2025

For years, the lithium-air battery has hovered at the edge of possibility, a promising idea that could one day store as much energy, kilogram for kilogram, as fuel.

Its appeal has always been clear: a battery light enough for electric aircraft to lift off confidently and powerful enough to carry an electric car far beyond the limits of today’s lithium-ion packs.

Yet despite the excitement, the chemistry stubbornly refused to cooperate. Early prototypes lasted only a few cycles, produced little usable power, or collapsed the moment engineers tried to scale them beyond tiny laboratory cells.

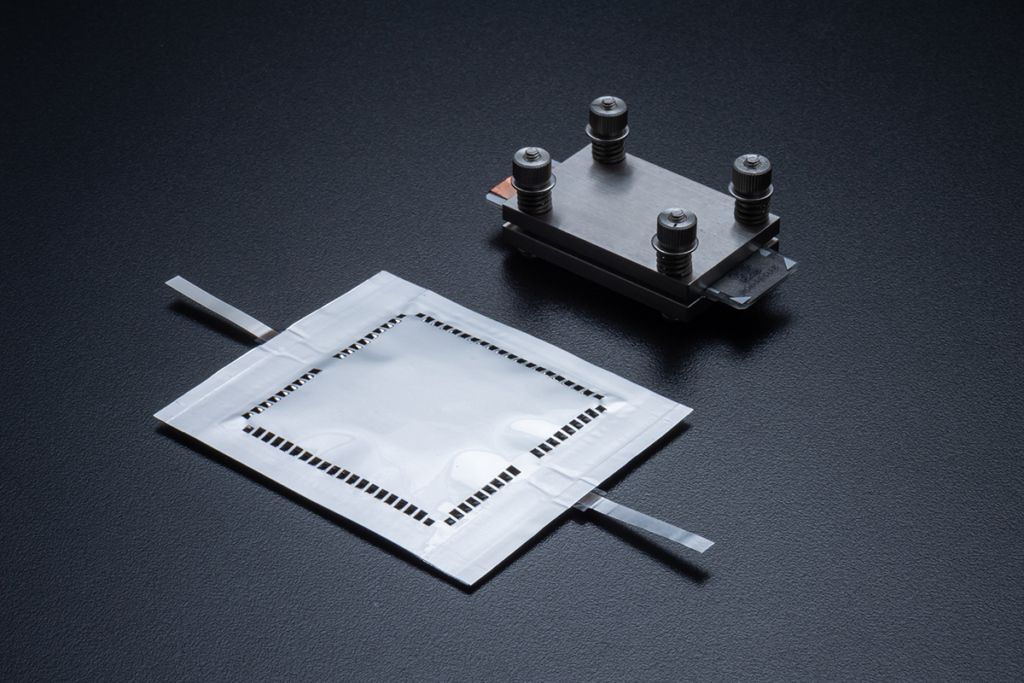

A team in Japan now believes it has finally cracked open the core problem. Scientists at the National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) and carbon-materials specialist Toyo Tanso have unveiled a carbon electrode that allows a lithium-air battery to operate at higher output, survive longer, and crucially, scale beyond the miniature coin-cell format that has defined the field for over a decade.

To demonstrate real-world potential, the researchers built a 1-Wh-class stacked lithium-air battery using a 4 cm x 4 cm electrode and ran it stably. The achievement is supported by detailed cell images, voltage curves and test methods presented in the published study.

Why lithium-air batteries could transform electric aircraft and eVTOL performance

The lithium-air concept is elegantly simple. Rather than storing oxygen inside the cell, the battery draws it from the surrounding environment. This slashes weight and, in theory, unlocks energy densities many times higher than those of standard lithium-ion cells.

NIMS showed a version surpassing 500 Wh/kg back in 2021, already well beyond typical EV batteries. But progress stalled whenever researchers tried to build something practical.

Most lithium-air cells were tiny, around 0.01 Wh, barely enough to power a hearing aid. They also suffered from three persistent flaws:

- low output, making them unsuitable for applications that require rapid bursts of power;

- short cycle life, as lithium peroxide clogged and damaged the carbon electrode;

- poor scalability, because the porous structures required for oxygen flow were nearly impossible to reproduce in larger, stable shapes.

This final issue has been the dominant roadblock. Designing a carbon electrode that could breathe oxygen efficiently, deliver high output and remain structurally sound at larger sizes required precise control over pore sizes at multiple scales.

Too many microscopic pores trapped the electrolyte. Too few macropores choked oxygen flow. Most previous attempts simply failed to find the balance.

Inside Japan’s breakthrough carbon electrode for next-generation lithium-air cells

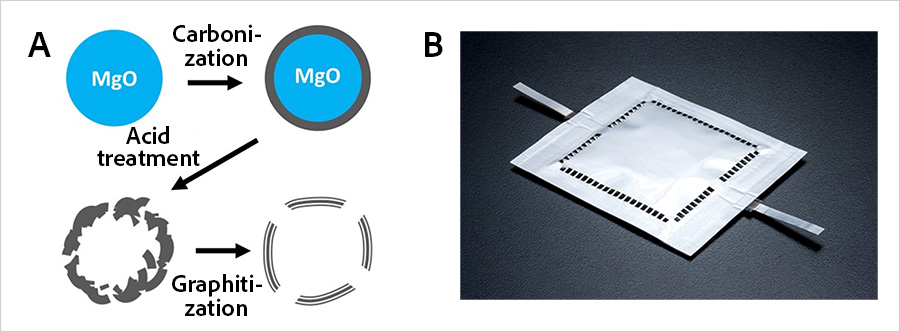

The NIMS–Toyo Tanso team approached the electrode as a structural engineering challenge. Technical diagrams in the paper show a layered, hierarchically porous carbon architecture designed to optimise oxygen transport while remaining chemically stable.

Toyo Tanso supplied its CNovel mesoporous carbon, known for its highly controlled internal structure. NIMS contributed its technique for producing self-standing carbon membranes, effectively thin, rigid sheets filled with a deliberately engineered pore network.

The result was an electrode that allows oxygen and lithium ions to move freely while resisting the side reactions that normally destroy lithium-air cells. Researchers also increased the carbon’s crystallinity, confirmed through X-ray diffraction, significantly improving durability during repeated cycling.

Testing showed the battery could achieve:

- stable cycling for more than 150 cycles at a demanding 1.5 mA/cm² current density;

- high output suitable for applications like electric aircraft take-off;

- reliable scalability, with consistent production of 10 cm x 10 cm electrodes, large enough for early industrial use.

How Japan’s 1-Wh lithium-air cell signals progress toward flight-worthy battery systems

With the new electrode, the team built a stacked lithium-air pouch cell using 4 cm x 4 cm layers. Test logs show the battery consistently delivering just over 1 Wh per cycle in a six-layer configuration, remaining stable for 19 cycles before reaching end of life.

By commercial standards, this remains small, but in the context of lithium-air research, it represents a genuine leap. Previous multilayer attempts rarely exceeded 0.3 Wh, and many failed outright because scaling crippled oxygen transport. This new approach demonstrates that larger cells can be built without suffering catastrophic losses in output or cycle life.

What this means for eVTOLs, electric aircraft and long-range EVs

If lithium-air cells can continue to scale while preserving their stability, they could reshape the future of electric flight and long-range EVs.

Aircraft developers, especially those working on vertical-lift concepts, need batteries that combine high energy with low mass. A future lithium-air pack could meet those demands.

For electric vehicles, the benefits are equally compelling. Today’s best EV batteries rarely exceed 300 Wh/kg, limiting long-distance capability. Lithium-air batteries could, in theory, offer energy densities approaching the effective energy per kilogram of petrol, transforming the economics and practicality of long-range electric travel.

The NIMS–Toyo Tanso milestone does not mean flying taxis or thousand-kilometre EVs will appear next year. But it does show that lithium-air technology can scale, deliver usable output, and survive repeated cycling, the three achievements it has never demonstrated together before.

Japan accelerates the global race for ultra-light batteries that could power future air taxis

The breakthrough also lands at a moment when research groups worldwide are exploring alternatives to conventional lithium-ion systems.

Last year, scientists at Monash University demonstrated a fast-charging lithium-sulphur battery that could one day power long-range EVs and commercial drones. That technology is now advancing toward flight-worthy prototypes.

Even so, lithium-air remains the most ambitious of the next-generation chemistries. With this new electrode, Japan has pushed the field toward something tangible, a technology that no longer exists only in coin cells and theoretical charts.

For the first time, a practical lithium-air battery feels a little less like a distant promise and a little more like a technology quietly taking shape for the next era of electric movement.