How were Concorde’s Rolls-Royce engines adapted for supersonic flight?

February 8, 2026

Imagine stepping off a nonstop flight in New York before the clock says you ever left London. Concorde made that apparent “time travel” possible by cruising at more than twice the speed of sound, slicing the transatlantic journey to just over three hours.

The experience began the moment the throttles were advanced for take-off. As the four Rolls-Royce Olympus engines spooled up and reheat ignited, passengers were pressed firmly back into their seats, a sensation far closer to a military launch than a conventional airliner departure. The acceleration was immediate and unmistakable, a clear signal that Concorde played by very different rules.

At the heart of that performance was the Rolls-Royce Olympus, a turbojet engine originally developed for high-speed military applications and extensively re-engineered for sustained civil supersonic flight. Unlike the high-bypass turbofans that power modern airliners, the Olympus relied on sheer exhaust velocity rather than mass airflow, trading fuel efficiency for raw speed.

Reheat, or afterburner, was integral to the design. Used during take-off and acceleration through the transonic regime, it delivered around 20% additional thrust, allowing Concorde to operate from existing runways despite its high take-off weights. Once established in cruise, the reheat was shut down, with the aircraft relying on efficient inlet pressure recovery to maintain Mach 2 flight.

Designed for a nominal 25,000-hour service life, the Olympus proved to be one of the most capable and durable turbojet engines ever to enter commercial service, bridging the gap between military propulsion and civil aviation in a way no other engine before or since has managed.

How Concorde’s Olympus engines were adapted for sustained supersonic cruise

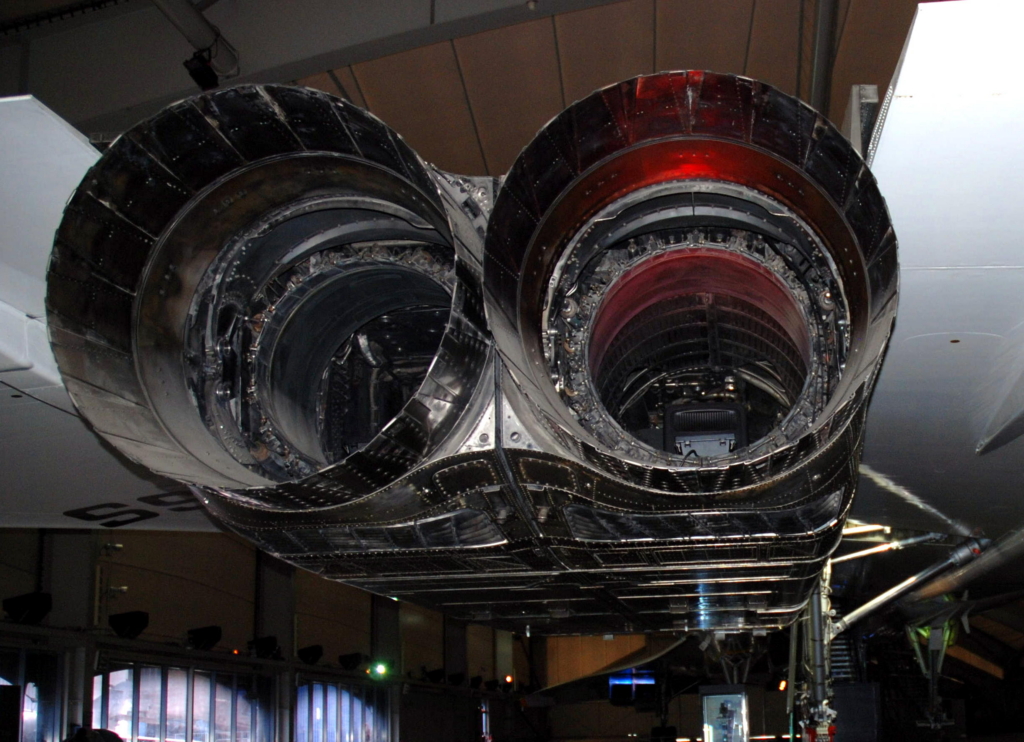

The Rolls-Royce Olympus used a dual-shaft turbojet layout with afterburner capability, a configuration more commonly associated with modern fighter aircraft than commercial airliners. This architecture allowed the engine to operate efficiently across a wide speed envelope, from take-off through sustained Mach 2 cruise.

Both the low-pressure (LP) and high-pressure (HP) compressors featured seven stages each, carefully matched to deliver air to the combustor at the optimal pressure and temperature. Each compressor was driven by its own single-stage turbine, separating low-speed and high-speed systems to improve efficiency and control at extreme operating conditions.

To survive prolonged supersonic flight, the engine’s compressor and turbine sections, including blades and vanes, were manufactured from advanced titanium and nickel-based alloys. These materials were selected specifically to withstand the intense thermal and mechanical loads generated during Mach 2 cruise.

Thermal management was equally critical. The Olympus employed a range of turbine blade cooling techniques, including film and impingement cooling, to prevent internal components from overheating and to maintain structural integrity at high temperatures.

While most major structural elements of the engine were designed for a 25,000-hour service life, some high-stress components operated on shorter cycles. Critical items such as turbine airfoils and liners typically require replacement after around 10,000 hours, reflecting the extreme environment in which the engine operated.

Modified air intakes reduced inlet airspeed and optimised pressure

The performance of a supersonic engine is greatly dependent on the speed at which airflow enters the engine inlet. Concorde’s engines were ingeniously designed to significantly lower the speed of incoming air. Even when the aircraft was at its cruising speed of Mach 1.6, the airflow rushing to the engine inlets remained at approximately 300 mph (Mach 0.4).

The inlet air pressure is another critical parameter that must be optimised for supersonic cruise. The Concorde featured a variable-geometry intake, allowing it to deliver air at varying pressure distributions based on compressor requirements.

| Concord’s Rolls-Royce Olympus engine | |

|---|---|

| Engine type | Turbojet |

| Compressor | 7-stage LP, 7-stage HP |

| Turbine | 1-stage LP, 1-stage HP |

| Maximum thrust per engine | 38,000 lbs (170 kN) |

| Overall pressure ratio | 15.5:1 stationary, 82:1 at Mach 2 |

| Thrust-to-weight ratio | 5.4:1 |

| Specific fuel consumption | 1.195 lb/(lbf.h) (33.8 g/(kN.s)) at cruise |

The variance in directional flow of the engine intake caused oblique shocks and isentropic compression in the supersonic flow. The shockwaves allowed supersonic pressure recovery, preventing excessive distortion and engine surging. The greater the number of shockwaves, the higher the pressure recovery.

Concorde reached 255 mph in under 30 seconds

Concorde’s four Rolls-Royce Olympus turbojet engines delivered a level of thrust unmatched by contemporary subsonic airliners. Together, they produced more than 150,000 lb of combined thrust, enabling the aircraft to accelerate from a standing start to 255 mph in less than 30 seconds.

This immense power was most evident during take-off and the climb through the transonic regime. Reheat was used to provide the additional thrust required to overcome rising drag as the aircraft approached the sound barrier, allowing Concorde to accelerate cleanly and continue its climb toward cruise at close to Mach 2.

Integral to this performance was the close integration between the Olympus engines and Concorde’s variable-geometry intake system. With the afterburner in operation, the intake not only managed airflow to the engine but also supplied cooling air to the hot exhaust nozzle, protecting components exposed to extreme temperatures.

The intake control system was designed to function seamlessly across the aircraft’s entire certified flight envelope, from take-off and subsonic cruise through sustained supersonic flight and on to approach and landing. By precisely regulating airflow and pressure recovery, it ensured stable engine operation while contributing directly to the aircraft’s overall handling and performance.

Featured image: Eduard Marmet / Wikimedia Commons