How a jet engine starts: The unseen dance of physics and software

November 15, 2025

Modern jet engines are some of the most complex machines in aviation. Yet they feature simplistic startup and operational procedures. A jet engine starts by ingesting high-pressure air from an external source into the starter.

The starter rotates the compressor and main engine fan blades. When the engine reaches a certain speed, fuel is injected into the combustor, and the fuel-air mixture is ignited. The combustion process forces turbines to spin at faster airspeeds, making the engine self-sustaining.

Detailed engine startup process

The jet engine startup sequence begins with the starter unit taking air from one of three external sources: the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU), a Ground Power Unit (GPU), or the cross-bleed.

The APU is a small turbine installed in the aircraft’s tail that delivers approximately 55 psi of air to the starter. The APU operates at a high speed to ensure adequate airflow into the starter.

Another source is a GPU, available through the ground service pneumatic connectors. Offering the nominal 45-50 psi air, the GPU is controlled through an external panel.

Cross-bleed air, generally required for in-flight restart, is the air source from the other (already operating) engine. The specific compressor bleed air is selected based on the engine’s operating speed. Generally, at lower engine speeds (idle to 75% maximum), the low-pressure supply check valve is open. Speeds greater than 75% maximum require opening the high-pressure supply check valve.

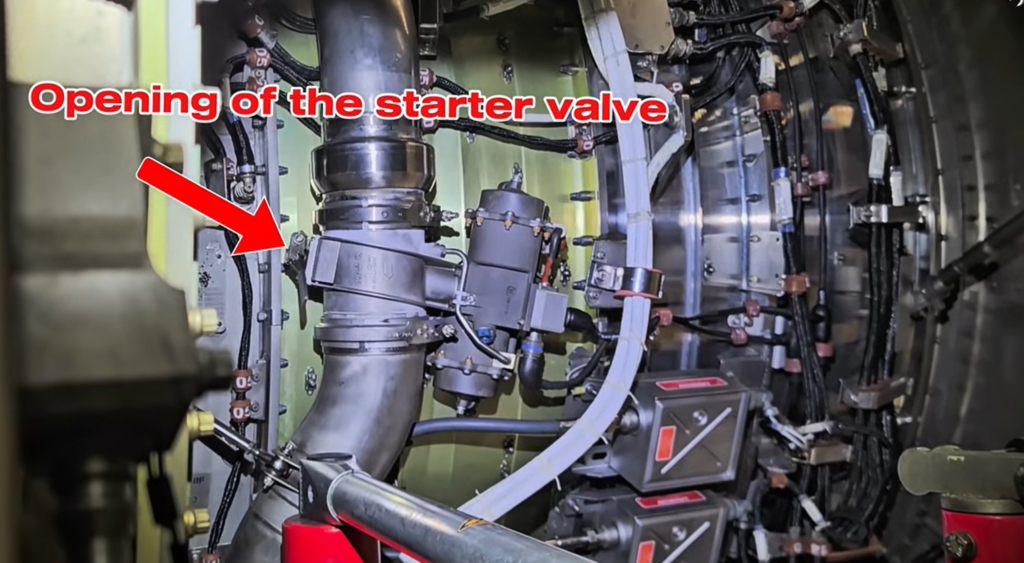

With the initial air source identified, pilots command the opening of the starter air valve, allowing pressurized air to spin the starter turbine. The starter is connected to the main engine’s shaft through a clutch. When the clutch is engaged, the N2 compressor shaft begins to rotate, subsequently spinning the fan.

When the rotation speed reaches approximately 20% of the maximum RPM, pilots command fuel injection. Pressurized fuel mixes with air in the combustion chamber. A powerful spark from the ignition system is activated to ignite the mixture.

Continuous combustion forces the main engine turbine to rotate at higher speeds, forcing an increased airflow into the engine. Once the engine is running at approximately 55% max RPM, it is time to disengage the starter from the engine shaft.

Technicalities of the startup system, equipment, and procedure

Modern engines are equipped with Full Authority Digital Electronic Control (FADEC), which allows the use of two processing channels. Each channel receives inputs and performs calculations separately. The channel whose calculations are supplying the output is called the active channel, and outputs that are terminated are from the standby channel.

A cross-channel datalink ensures both channels always remain up to date and any errors are averaged out. If a component on the active channel malfunctions, data from the standby channel can be used for output. If a major system on the active channel malfunctions, the standby channel becomes the new active channel for all processes.

In case of a malfunctioning starter system, ground personnel can manually turn the starter air valve to the open position. In such cases, the valve must also be turned off manually. Failure to disconnect the starter when the engine is self-sustained may result in starter damage. Some operator procedures may require a complete shutdown of the affected engine.

Featured Image: LETISKO VIEDEŇ-SCHWECHAT / YouTube