NASA and Boeing test longer, smarter wings for more efficient future airliners

December 19, 2025

Engineers at NASA and Boeing are working on wings that look very different from those passengers are used to seeing today. Longer, slimmer and more flexible, they are designed to slice through the air with less drag and greater efficiency.

For airlines facing rising fuel costs and tightening climate targets, these changes are not about aesthetics, but about efficiency, range and passenger comfort.

At NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, engineers working with Boeing believe longer, thinner wings could play a central role in that shift. Known as high-aspect-ratio wings, the design reduces drag and improves lift, helping aircraft burn less fuel. But the concept comes with a challenge: flexibility.

“When you have a very flexible wing, you’re getting into greater motions,” said Jennifer Pinkerton, a NASA aerospace engineer. “Gust loads and manoeuvre loads can excite the wing more than on today’s designs. Our goal is to keep the efficiency benefits while controlling how the wing responds.”

The problem with long wings: Flutter and vibration

Without careful engineering, long wings can bend excessively or enter a dangerous condition known as flutter. Flutter occurs when airflow interacts with the wing structure in a way that amplifies vibrations, potentially leading to catastrophic failure.

“Flutter is a very violent interaction,” Pinkerton explained. “The oscillations can grow exponentially if they’re not properly controlled. Part of our job is to understand those instabilities so they can be avoided entirely in real flight.”

To address this, NASA and Boeing launched the Integrated Adaptive Wing Technology Maturation programme, which focuses on actively controlling wing motion. The aim is to soften the impact of gusts, reduce structural loads during turns, and suppress flutter, while preserving fuel savings and improving passenger comfort.

How NASA and Boeing are testing flexible aircraft wings in wind tunnels

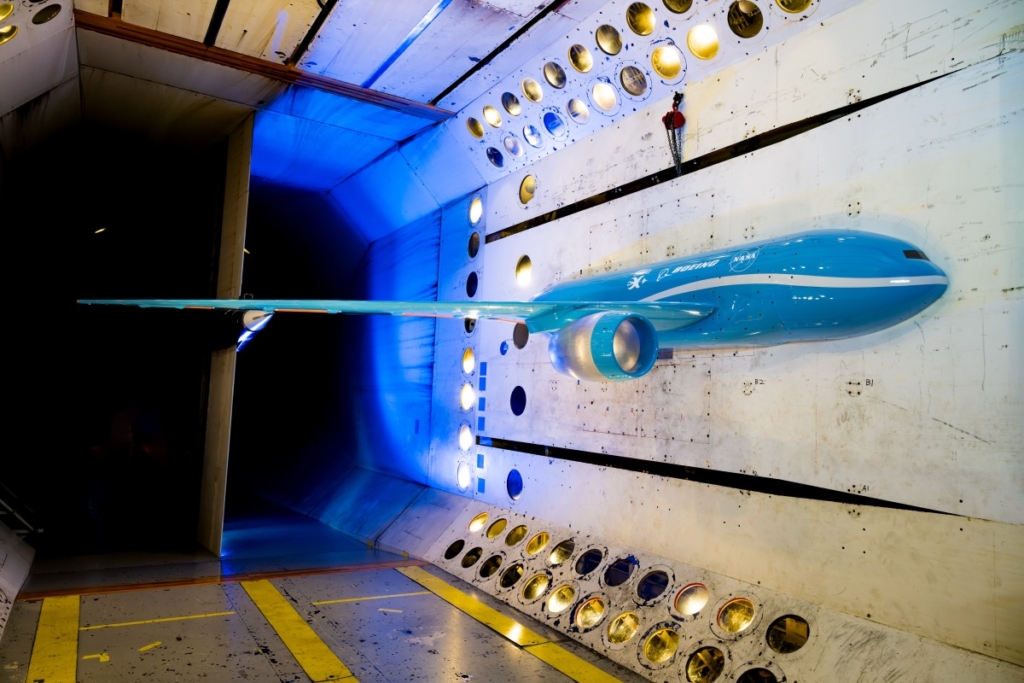

Full-scale testing on a commercial airliner is impractical, so the team turned to NASA Langley’s Transonic Dynamics Tunnel, a facility that has shaped US aircraft design for more than 60 years. Its large test section allows researchers to study realistic wing behaviour using advanced scale models.

Working with NextGen Aeronautics, NASA and Boeing built a highly detailed half-aircraft model with a single 13-foot wing. Along the trailing edge, engineers installed ten movable control surfaces, allowing them to fine-tune airflow and counteract vibrations in real time.

Sensors embedded throughout the model measured aerodynamic forces and structural responses as wind speeds and gust conditions were varied. By adjusting the control surfaces, researchers were able to significantly reduce wing motion, particularly during simulated turbulence.

“This model is much more complex than what we used before,” said Patrick S. Heaney, NASA’s principal investigator for the programme. “Earlier tests had two active control surfaces. Now we have ten, which lets us explore far more advanced control strategies.”

Initial tests in 2024 established baseline data, while a second campaign in 2025 focused on active control techniques. The most visible gains came during gust-alleviation trials, where wing movement was sharply reduced.

Why airlines are backing new aircraft designs and efficiency technologies

The research comes as airlines worldwide reassess what the next generation of aircraft should look like. With fuel efficiency, emissions and operating costs under increasing scrutiny, carriers are becoming more open to unconventional designs that promise long-term savings.

From ultra-efficient narrowbodies to hybrid-electric and short-take-off aircraft concepts, airlines are signalling a willingness to invest early in new technology.

In India, carriers such as SpiceJet have announced they are exploring next-generation aircraft platforms as part of broader efforts to improve efficiency and reduce operating costs, reflecting a wider industry trend rather than a single technology bet.

Longer, adaptive wings fit squarely into that picture. If successful, they could allow future jets to fly farther on the same amount of fuel, operate more quietly, and deliver a smoother ride through turbulence, benefits that appeal equally to airlines and passengers.

How adaptive wing research could reach future commercial aircraft

With wind-tunnel testing now complete, NASA and Boeing are analysing the data and preparing to share their findings with aircraft manufacturers and the wider aviation community. The results will help designers decide which technologies are ready to move from research programmes into real aircraft.

“Initial data analyses show that the controllers we tested delivered large performance improvements,” Heaney said. “We’re excited to continue analysing the data and sharing the results in the months ahead.”

The work forms part of NASA’s Advanced Air Transport Technology project under its Advanced Air Vehicles programme, which aims to shape the aircraft of the future. For travellers, the payoff may one day be felt rather than seen: quieter cabins, gentler flights, and airliners that use less fuel to go the same distance.

As airlines invest in new aircraft ideas and engineers push the boundaries of wing design, the humble wing, longer, thinner and smarter, could become one of the most important features of tomorrow’s airliners.

Featured image: NASA