Coverage isn’t enough: Why Europe’s IRIS² must prioritise resilience in contested space

February 14, 2026

Martin Halliwell is a partner at NewSpace Capital, a private equity fund investing in high-growth space companies. He previously served as Chief Technology Officer of SES, where he led global technology and R&D from 2011 to 2019, overseeing the development and deployment of advanced satellite systems.

Dr Robert Brull is Chief Executive Officer of German advanced materials company FibreCoat. FibreCoat is a global leader in the development of ultra-resilient, conductive and lightweight materials used in applications ranging from spacecraft and military decoys to chaff for fighter jets and next-generation aerospace systems.

Daily, we are reminded that European strategic autonomy is a necessity. And that’s why IRIS² is significant: it will help the bloc to secure its communications in an increasingly dangerous world.

The ambition is to establish reliable satellite connectivity for governments, defence forces, and emergency response operators, and have it all under European control. That is a good ambition to have. But ambition alone will not carry the system through a real crisis.

Space is no longer a benign environment

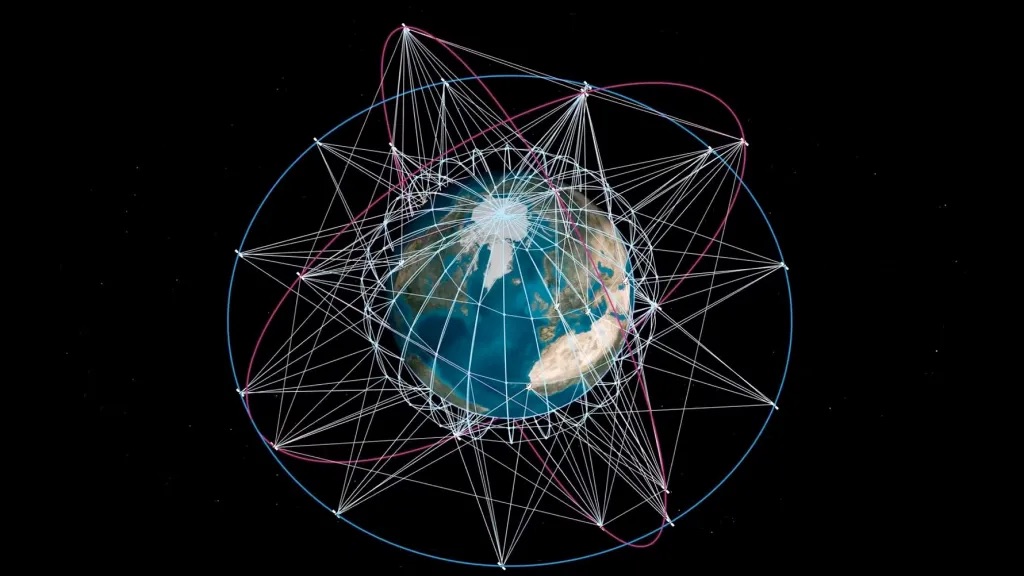

We don’t have to imagine the sorts of threats that IRIS², with its almost 300 satellites, is likely to face. They’re plain to see.

Around the world, satellite communications are being jammed, spoofed, hacked, and degraded.

In Iran, the government has engineered a near-nationwide blackout using highly sophisticated technology. In Ukraine, space-based systems have been targeted as part of routine military operations.

For decades, the Outer Space Treaty rested on the assumption that space would remain a largely benign, non-hostile environment. That assumption no longer holds.

Satellite communications are now routinely jammed, spoofed, hacked, and degraded. In case there was any doubt left in the mind of the observer, space is very much a contested domain.

Coverage versus resilience in satellite constellation design

Thus, the brutal reality is that any system developer or operator who assumes space is the benign environment it once was is already on the way to making their work obsolete.

So we’re forced to wonder why so much of the public conversation around IRIS² still centres on coverage maps, industrial return, and institutional ownership. Of course, these matter; but do they address the central question? Will the system still work when someone is actively attempting to bring it down?

We know how satellites can be attacked. Hostile actors can jam radio frequencies and overwhelm signals; they can hack into and corrupt control systems on the ground; they can mislead users through spoofing; and – the brute force option – they can directly damage or destroy spacecraft.

Hence, a constellation designed primarily with coverage and sending a political signal in mind risks failing to succeed on its own terms.

The risk of prioritising cost over satellite resilience

Making things worse are some of the prevailing design habits of satellite manufacturers. These manufacturers typically build satellites, particularly the small, low-cost satellites, to be cheap, light and quick to launch.

That approach has benefits: it has cut costs and increased access to space. The problem is that it often comes at the expense of resilience, durability and longevity. That might represent an acceptable trade-off in a benign, commercial setting. But it certainly isn’t when the system in question is expected to reliably support, defence, security and crisis response.

This is the temptation that the developers of IRIS² must avoid. If they cut corners in respect of resilience, then the whole fleet of satellites will struggle to keep running in a contested or denied orbital setting. That is not hypothetical, but the most likely hurdle the system will have to overcome.

Resilience as a core requirement for IRIS²

Resilience, therefore, has to be treated as a basic design requirement, not an optional extra.

A resilient satellite that can survive both the inherently harsh physical environment of space and the efforts of hostile state actors, that can resist jamming and spoofing, is one that will enable the system to keep going and doing what it is supposed to.

So resilience should be understood in terms familiar from cybersecurity: defence in depth. No single safeguard is sufficient. Instead, multiple layers – hardware, software, signals, and network design – work together so that if one fails, others compensate.

A happy side effect of this pertains to what happens after a crisis. When satellites are built to last, fewer replacement satellites and so fewer launches are necessary. That cuts costs over time. It also reduces debris, which threatens all spacecraft. Durability and sustainability thus go together.

Procurement reform and adaptability in European space programmes

There is a further risk that merits our attention: procurement. Large public programme decision-makers have a natural tendency to favour legacy ways of doing things and a narrow group of established prime contractors.

That might feel safe, but it also locks in designs that are slow to adapt and hard to upgrade. And adaptability is vital to resilience. It should go without saying that threats change, technology grows in sophistication, and materials improve. So IRIS² must involve an approach to acquisition that reflects that reality.

Europe’s various defence and space strategy documents make liberal use of the term ‘resilience’, as well as ‘preparedness’ and ‘autonomy’. That’s a good thing. But few of the official communications and industry briefings around IRIS² specifically put these front and centre.

It is important that the project is framed clearly and explicitly as a programme that makes resilience as important, if not more important, than coverage, sovereignty and other considerations.

The good news is that Europe has considerable expertise and experience in providing just what the constellation needs to guarantee that it will continue to run regardless of the threats it faces.

We have some of the world’s leaders in advanced materials development and systems engineering. There are companies that specialise in making spacecraft tougher, lighter and more resistant to damage without breaking the bank.

Why IRIS² must prove Europe can operate in contested space

At a time when it seems increasingly likely that Europe and the United States will go their separate ways for a time in certain key respects, Europe must send a message to its adversaries and potential aggressors that it understands the complexities of modern conflict and is not a soft target, but a continent that can protect itself and its assets.

That would also signal to the public that their money is being spent wisely: on systems that will work today, tomorrow and the day after that – not ones that worked 10 years ago.

Space has changed. Launch is routine; survival is not. The real test is whether systems keep working under pressure. IRIS² gives Europe a chance to prove it can build communications infrastructure that lasts, adapts, and remains operational in hostile conditions.

To do that, resilience and longevity must be written into requirements from the start – not treated as trade-offs later. Governments should specify them. Prime contractors should design for them. And Europe should draw on its emerging industrial expertise to gain a real edge.