Royal Netherlands Air Force trials AI simulators that adapt to pilots’ brain activity

February 7, 2026

What if a flight simulator could tell when a pilot is struggling or getting bored, and adjust itself instantly?

That idea sits behind a new training system being tested in the Netherlands, where artificial intelligence reads trainee fighter pilots’ brain activity and alters virtual missions in real time.

The concept marks a sharp break from traditional military flight training. For decades, instructors have relied on fixed lesson plans, increasing difficulty in preset steps and judging progress through performance alone.

This new approach replaces that structure with something more personal: training that responds continuously to how demanding a task feels inside the pilot’s own head.

Early trials suggest trainee fighter pilots prefer this adaptive style of training. But the research also delivers a less intuitive conclusion. While pilots like the system, it does not yet make them better at flying.

Why flight simulators need to adapt, not just simulate

Training fighter pilots is expensive, risky and increasingly constrained. Every hour flown consumes fuel, airframe life and maintenance resources.

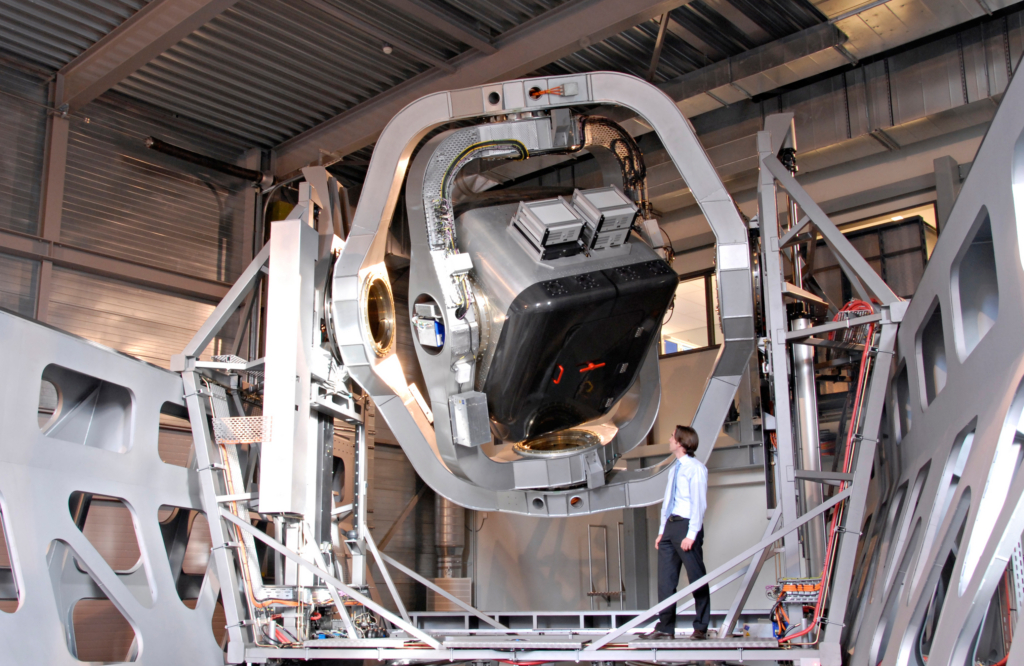

As a result, simulators and virtual reality (VR) environments now play a central role in teaching everything from basic handling to combat procedures.

Yet simulators present a familiar problem. Training has to hit a narrow mental “sweet spot”. Tasks that are too easy breed complacency. Tasks that are too difficult overwhelm trainees and halt learning altogether.

Traditionally, instructors manage this balance by designing scenarios that grow harder in fixed stages. Everyone progresses along the same path, regardless of how quickly or slowly they adapt.

The Dutch research set out to test whether that balance could be managed automatically, using real-time data from the pilot rather than assumptions built into a syllabus.

Using brain activity to adapt flight simulator training

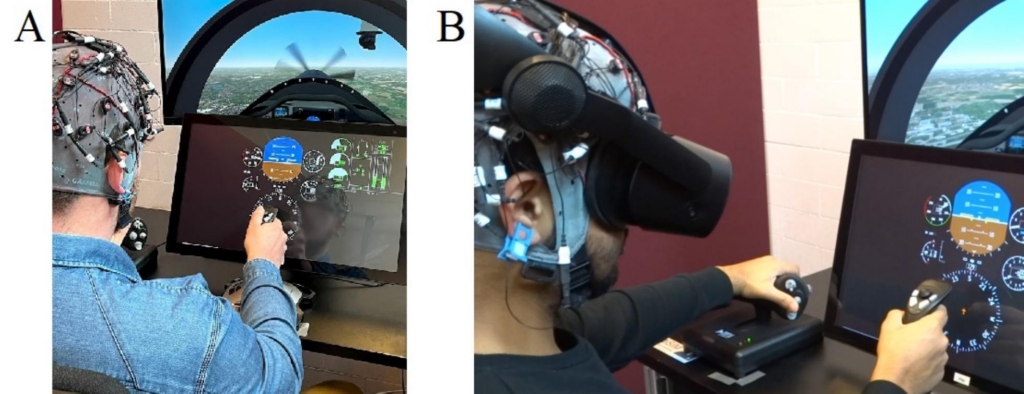

The work was led by Dr Evy van Weelden and her team at the Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre in Amsterdam. Their system uses a brain–computer interface, or BCI, which measures electrical signals in the brain through electrodes placed on the scalp.

As trainee pilots fly VR missions, an AI model analyses those signals to estimate cognitive workload, effectively judging how mentally demanding the task is at any given moment. The system does not attempt to read thoughts. Instead, it looks for patterns associated with mental strain or relative ease.

That assessment then drives the simulator. If the AI determines a pilot is becoming overloaded, the next mission becomes easier. If the workload appears low, the difficulty increases.

“If you’re not in the field, it sounds very sci-fi,” Dr van Weelden tells New Scientist. “But for me, it’s normal. I just see data.”

How researchers tested AI-driven pilot training

Fifteen trainee pilots from the Royal Netherlands Air Force took part in the study. Each flew multiple VR missions under two different training conditions.

In one, difficulty followed a conventional, pre-programmed progression. In the other, the AI adjusted difficulty dynamically across five levels, based entirely on brain activity.

Rather than introducing complex system failures, the researchers manipulated visibility. Clear conditions represented the easiest level, while fog, degraded visual cues and misleading horizons created progressively harder scenarios.

Crucially, pilots were not told when the system was adjusting difficulty, or even that it was doing so at all.

Pilots preferred AI-driven flight simulator training

After the sessions, pilots were interviewed. None reported noticing that the simulator had been changing difficulty levels in real time. From their perspective, the missions simply felt different.

When asked to compare the two approaches, ten of the fifteen pilots said they preferred the adaptive system. Several described it as more realistic and less predictable, closer to real flying, where challenges do not arrive in neat, planned increments.

One pilot noted that in conventional training, “you know what’s coming next”. In the adaptive system, that predictability disappeared.

From an instructional standpoint, the feedback matters. Engagement, realism and motivation are all valued in military training environments.

But adaptive flight simulators did not improve pilot performance

Despite that positive response, the performance data told a more sobering story.

Across multiple measures, including task accuracy and aircraft control, the researchers found no meaningful difference between pilots trained with the adaptive system and those using the rigid, pre-set programme.

In short, pilots liked the brain-adaptive training, but it did not improve how well they completed the tasks.

The researchers believe the limitation lies in the complexity of the human brain itself.

Why AI struggled to interpret pilot brain signals

The AI model was trained on brain data from a separate group of novice pilots before being applied to the fifteen participants. While it worked well for some individuals, it struggled with others.

Six pilots showed almost no variation in detected workload across missions, suggesting the system was not interpreting their brain signals accurately at all.

The system also reduced workload into broad categories, which may not capture subtle differences between visual strain, decision-making pressure and spatial disorientation.

Could brain-reading AI move from simulators to cockpits?

Similar ideas are being explored beyond simulators. New Scientist quoted James Blundell of Cranfield University as saying researchers are studying whether aircraft systems could detect pilot stress or startle responses in real time.

In theory, an aircraft could recognise when a pilot is panicking or disoriented and respond by highlighting critical information or guiding them back to stable flight.

Such systems have shown promise in isolated experiments. But Blundell cautions that translating brain-reading technology into operational aircraft remains a long way off.