While the late-2023 release of the question-answering, essay-writing, text-generating robot known as ChatGPT may have brought sudden and widespread awareness of the disruptive potential of so-called artificial intelligence, it should come as no surprise that government and industry have been grappling for years with the implications of AI technology. Indeed, the issue was the subject of a keynote address and panel session at the Connected Places Summit, held in London on 20-21 March.

As Alex Mindell, head of AI and autonomy in the science, innovation and technology division at the UK’s Department for Transport, observed, AI first came to prominence way back in 1997, when IBM’s “Deep Blue” system played chess grand master Gary Kasparov – and won. But Mindell went on to note that there has been a huge amount of AI progress since then, and the general-purpose systems seen today pose very different opportunities and risks than “narrow” algorithms like Deep Blue, which are built to excel at a particular task.

But like Deep Blue, today’s AI systems rest on what Mindell called the “building blocks” of data, algorithms and computing power. As the panel discussion which followed Mindell elaborated, all three of those blocks are increasingly supercharged, opening the prospect of impressive benefits to our transport systems.

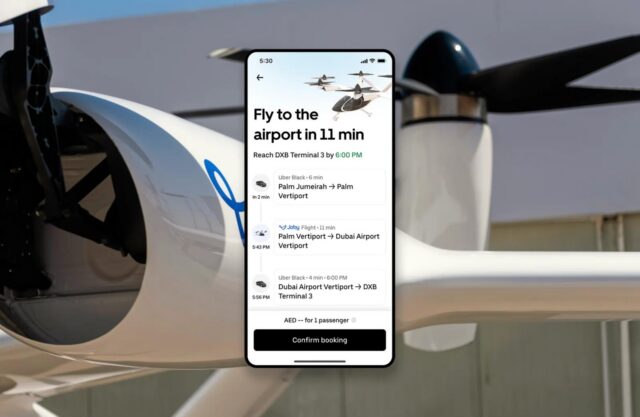

Given enough high-quality data, there may be great benefits to realise by exploiting AI in the transport system. AI schemes to optimise travel, for example by better aligning the links in multi-modal journeys, promise to save time and money. An application which particularly excites AI experts is self-driving vehicles, given their potential to mitigate the influence of that safety weak link known as human drivers.

But what about airplane pilots? The panel didn’t specifically address aviation, so FINN caught up with one of the participants, Gopal Ramchurn (pictured), professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Southampton, to find out what he thinks is coming in the cockpit.

In particular, we asked Professor Ramchurn if AI systems, which are often described as “black boxes” that reveal little of the “reasoning” behind their outputs, can be compatible with aviation’s safety culture. That is, are inscrutable black boxes at odds with the practice of investigating every incident in granular detail to work out what went wrong and how to prevent a recurrence.

Professor Ramchurn’s response is that these systems are not as inscrutable as widely believed; investigation can shed much light on the question of whether the technology failed.

The AI research community, he notes, is particularly interested in the fatal 2018 crash of an Uber self-driving car prototype, which struck and killed a woman wheeling a bicycle despite the presence of an on-board human back-up driver.

To illustrate his greater concern, Professor Ramchurn notes that aviation has for years been introducing automation and he flags up the two fatal Boeing 737 Max crashes, Lion Air Flight 610 on 29 October 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on 10 March 10 2019. A factor which links all of these tragedies is the assumption that a human driver or pilot would be able to take control if needed.

Unfortunately, he says, to rely on “human ability to take control at machine speed is an unfair ask of the human”.

He believes that the challenge now is to build AI systems differently. That is, AI systems must be designed around how humans behave and respond. And further, he adds, to build a system around the reaction time capabilities of the average human is another mistake: “There is no average human!”

Or put another way, he says, “AI must be mindful of human users.” That is, public perception of safety is crucial, a point which aviation has covered well for many years.

So, to take advantage of the safety and efficiency gains that AI might bring to aviation, Professor Ramchurn cites three requirements: regulation with a focus on reassurance, thoughtful deployment and, at least for the foreseeable future, human pilots in the cockpit – no remote control.

Ultimately, he says, it’s a question of when, not if, more AI systems can be introduced without undermining passenger confidence: “Aviation will be safer with AI systems.”

Subscribe to the FINN weekly newsletter