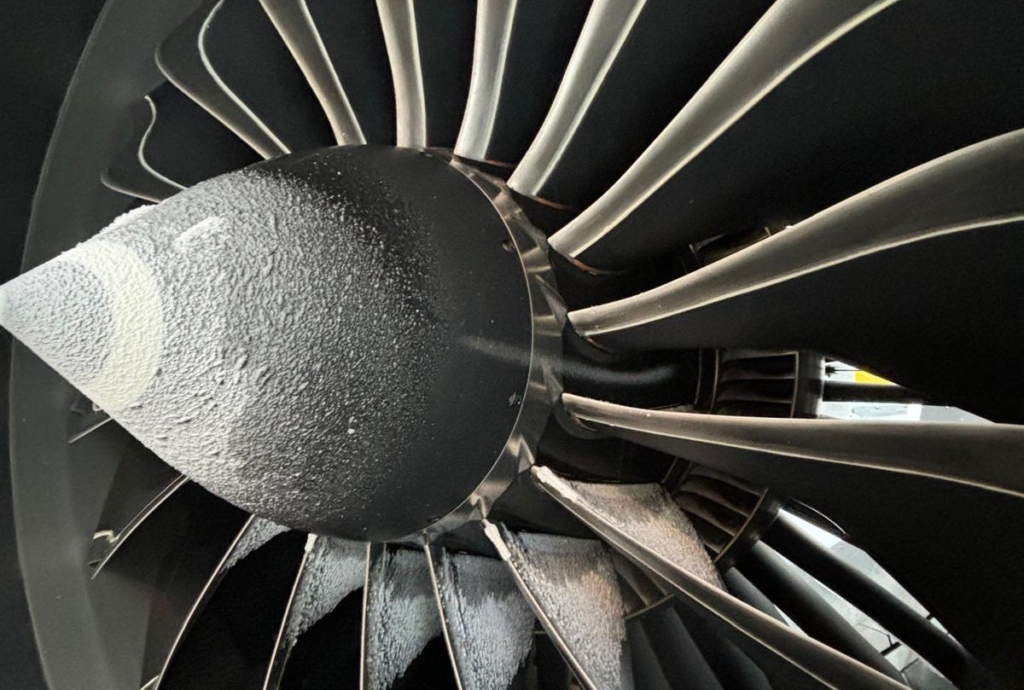

Why don’t aircraft engines have screens or grills?

December 24, 2025

Given the obvious risk of birds, debris and other loose objects being sucked in, it seems like some form of protective screen or grill would be a no-brainer.

Yet, across commercial aviation, exposed engine inlets remain the norm – and for good reasons rooted in safety, physics and efficiency.

Engine airflow efficiency comes first

At the most basic level, jet engines are designed to move vast quantities of air as smoothly and efficiently as possible. In fact a modern high-bypass turbofan can ingest several hundred kilograms of air per second.

Any obstruction placed in front of that airflow, even a thin grill, would disturb the carefully engineered aerodynamics of the inlet.

Disrupted airflow can reduce engine efficiency, increase fuel burn, and in worst cases lead to compressor stalls or surging.

Why could screens increase the risk of engine damage?

Screens or grills themselves would add another hazard simply because they’re something else than can go wrong or fail.

Foreign object damage (FOD) is a known danger, but manufacturers design engines to tolerate and survive bird strikes and small debris ingestion.

Engine certification standards mean modern jet engines must be able to ingest birds of specific sizes without failing catastrophically. But if a screen or grill was to be struck by a bird or debris at high speed, fragments of the grill could be ingested by the engine. This would create far more severe damage than the very thing it was meant to stop.

Are there times when screens are needed?

Screens over the engines still have their place, for example, engines occasionally have screens put over them during engine testing on the ground.

Also, when the aircraft is sitting at gate or on the airfield, the engines may be temporarily covered by intake covers (or “intake blanks”) to prevent ice and snow from getting in.

Many turbine helicopters also have screens over the air intake (and some have air particle separators) for use in dusty or sandy environments.

Weight and fuel efficiency matter too

Weight and balance is another critical factor. Even a relatively light protective structure adds mass, and in aviation every kilo counts.

Additional weight directly affects fuel efficiency, range and payload capacity. Over the lifespan of an aircraft, even minor increases in fuel burn translate into significant operational costs and higher emissions – outcomes the industry works hard to avoid.

Maintenance and reliability issues

Maintenance and reliability concerns further argue against screens. Engines operate in extreme conditions, facing temperature changes, moisture, ice and contaminants. A grill would need regular inspections and cleaning to make sure it remains free of ice, dust or residue.

Ice in particular could block airflow or shed unevenly, creating vibration or imbalance at the engine face. Not having a screen avoids these complications entirely.

How do airports reduce foreign object damage risk?

Reducing foreign object damage reaches further than just aircraft engines. Airports enforce strict FOD control procedures, runway inspections and wildlife management programmes.

From grass height control to bird deterrence systems, much of the risk is managed at the airport level rather than on the aircraft itself.

As just one example, after investigators confirmed bird strike evidence in the 2024 Jeju Airlines crash, it was reported that South Korea ordered all airports to install bird-detection cameras and thermal imaging radar systems.

Deliberate design

In the end, the open engine inlet is not an oversight but a deliberate aircraft design choice. Through rigorous certification, innovative engine design and various different operational safeguards, an unobstructed airflow path is the safest, most efficient solution.

Get all the latest commercial aviation news on AGN here.

Featured image: Ryanair