COVID-19 and MRO: four certainties among the “known unknowns”

David Stewart, Partner at Oliver Wyman, with fellow Partners Ken Aso, Dennis Santare and Chris Spafford explores post-pandemic certainties, uncertainties and challenges ahead for the MRO industry

It is blindingly…

David Stewart, Partner at Oliver Wyman, with fellow Partners Ken Aso, Dennis Santare and Chris Spafford explores post-pandemic certainties, uncertainties and challenges ahead for the MRO industry

It is blindingly obvious that the aerospace industry is in the most economically challenging period of its entire history. The current crisis is deeper and broader than any prior bumps in the road of growth, such as 9/11 or the 2008 global financial crisis. The degree of uncertainty over what will happen next has raised big questions around, for example, the parked fleet and prospects for used serviceable material (USM), the timing of recovery and post-COVID OEM strategies, among others.

Common themes and certainties arise

But whilst the level of “known unknowns” continues to be high, we believe that there are now a number of common themes or certainties that aerospace and aftermarket players can start to plan around. Here are four examples:

- Certainty 1: The short-haul/narrow-body market will recover first. Moving forward, narrow-body aircraft will account for an increasing share of the total fleet.

- Certainty 2: The era of the four-engine (passenger) aircraft is in decline. Future prospects for the A380, 747-8 and A340 fleets are niche at best.

- Certainty 3: Aftermarket demand (MRO spend) will recover more quickly than other aviation measures, such as RPKs. Engine and airframe maintenance activity which was deferred in 2020 – for good reason – has to be done at some point, so a catch up will happen.

- Certainty 4: As flying recovers, demand will increase for replacement parts. Airlines will be looking for low-cost options, such as USM. As there is a record level of feedstock aircraft available for teardown, we expect a concomitant bow wave of USM demand.

What is less certain are the answers to two big questions:

- Will the COVID-19 crisis cause permanent changes to the industry, and if so, what changes will be the most critical?

- Has the crisis weakened the aerospace industry’s ability to respond to the climate change challenge?

Whilst mid-crisis, the industry has a tendency to believe that things will never be the same again. In past crises, life mostly returned to normal and industry structure changed little. This time around may be different, however, given the far deeper and longer impacts of the COVID pandemic. In no order of priority, we anticipate that three significant changes are likely to be permanent.

A shift in balance of power in aerospace design and development

First, the balance of power in the aerospace design and development ecosystem will shift. This hypothesis is founded on two main observations. One is that the airframe OEMs have been weakened financially in the crisis. This will restrict their level of ambition, for example, their willingness/ability to spend on (and the timing of) the next new-generation platform. The other observation is that regulatory and certification stringency for new technology is likely to increase, driven by the MAX experience. The upshot is that any new “moon-shot” aircraft are unlikely in this decade. Technology improvements for new large platforms will be incremental and likely driven by three levers: propulsion, digital and weight. IP and expertise, particularly for the first two, belong to the engine and component OEMs. Airframers will have to rely more heavily on such partners for new programmes moving forward.

Rapid movement towards net-zero carbon emissions

Second, momentum is rapidly increasing for the world to move to net-zero carbon emissions. The COVID-19 crisis, however, has implicitly reduced the aerospace sector’s ability to respond to this challenge. With aviation at increasing risk (especially in Europe) of regulatory intervention, we expect to see increased investment focus on alternative fuels to power existing larger gas turbine engines and on hybrid-electric solutions for smaller platforms where the limited power density of batteries is less of a constraint.

Business models will adapt to a “new chapter”

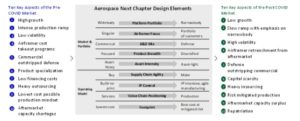

Third, aerospace suppliers will need to evolve their business models to adapt to a “new chapter” and build in greater resilience in a post-COVID market.

To thrive in a post-COVID world, firms will need to adapt their addressed markets and portfolios to recognise realities such as the dominance of the narrow-body fleet, the comparative inherent stability of the defence market and the benefits of a diverse customer base and product range. Airlines will look to lower capital costs and variabilise fixed costs, meaning that asset-light solutions will be increasingly sought after.

Similarly, operating models will evolve, seeking the right balance of IP control, make/buy decisions and production footprint. Lowest cost-focused production solutions will move to best cost, mitigating risk by moving facilities closer to home. The pace of globalisation has likely slowed.

The aerospace sector is resilient and we have no doubt that it will recover, although at what pace remains uncertain. Fortunately, there are certainties and realities that can be embraced even now to begin shaping strategic decisions for future business resilience.

- Video: before the pandemic FINN caught up with David Stewart to talk about how the industry would be forced to adapt to the issue of aircraft groundings

Subscribe to the FINN weekly newsletter